Synthesising indegenious motifs and ideas in video art: a study of uli and nsibidi motifs

Table Of Contents

Title Page………………………………………………………………i

Certification……………………………………………………………ii

Approval page………………………………………………………….iii

Dedication page…………………………………………………………iv

Acknowledgements……………………………………………………..v

Abstract….………………………………………………………………x

List of figures……………………………………………………………xi

List of plates……………………………………………………………xiii

Chapter ONE

: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………..….1Background to the Study…………………………………………………………….1

Statement of the Problem……………………………………………………………6

Objectives of the Study………………………………………………………………6

Significance of the Study……………………………………………………………..7

Scope of the Study…………………………………………………………………….8

Limitations…………………………………………………………………………….8

Research Methodology………………………………………………………………..9

Organisation………………………………………………………………………….10

viii

Chapter TWO

:LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………11Video Art, a Conceptual Delineation…………………………………………………12

Animation as a Contemporary African Art Form…………………………………..16

Indigenous Motifs, its Socio-cultural Significance…………………………………..19

Selected Nigerian Motifs: Uli and Nsibidi ……………………………………………21

i. Uli motif…………………………………………………………………………21

ii. Nsibidi……………………………………………………………………………25

Adaptation of Uli and Nsibidi motifs by Selected Nsukka Artists……………………27

A Historical Survey of Selected Artists and Their Works……………………………30

Video Art in Africa: Conceptual Developments since 1980………………………… 33

i. The period, 1980 to 1989 …………………………………………………………33

ii. The period, 1990 to 1999………………………………………………………..34

iii. The period, 2000 to present…………………………………………………….35

New Directions of Video Art from Africa: A Harvest of Fresh Budding Artists…..37

Chapter THREE

: PROCEDURE AND PRESENTATION OF WORKS……….43A. Tools and Materials…………………………………………………………………..43

B. Working Process………………………………………………………………………45

C. Study for Uli/ Nsibidi Motifs…………………………………………………………47

D. Selected Studio Sketches…………………………………………………………….49

E. Drawings for Animation………………………………………………………………51

i. Storyboard Sketches for Video

art………………………………………………56

F. Working Process For Creative Photography………………………………………..60

Chapter FOUR

: ANALYSIS OF WORKS…………………………………………63A. Animation…………………………………………………………………………64

B. Video Art/ Video installation…………………………………………………….68

C. Creative Photography…………………………………………………………….72

D. Visual Communication Designs………………………………………………….80

ix

Chapter FIVE

: CONCLUSION………………………………………………………87REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………………….89

APPENDIX…………………………………………………………………………………92

Thesis Abstract

Recently, video art concepts in Africa have been haunted by tentacles of

universalism, transculturation and acculturation that threaten their socio-cultural

thresholds prospectively. The implication of this includes a muted indigenous

voice and the possibility of the genre not being indigenously personalised by

African artists in the course of its development. The intent of this research is to

address this. Methodologically, it is strictly but flexibly constrained to video art

footages that are sometimes depicted in the form of animated drawings. Nsibidi

and uli motifs have been chosen because of their aesthetic and functional

qualities. Finally, the strategic approach adopted in the organisation of the study

is the researcher’s attempt to justify and satisfactorily contain the vast nature of

its subject matter.

Thesis Overview

INTRODUCTION

Background to the Study

African art has been in contention with the growing challenges and influences

imposed on it by western perspectives on modern art over the years. Among other factors,

these challenges are sometimes associated with the ideal indigenous creative communication

pattern and its adaptation to this burgeoning global art phenomenon without characterising a

compromised cultural inflection. One cannot ostracize the fundamental role culture plays in a

society. It is a vital aspect of a people’s very humanity and identity (Teaero, 2002). In Africa,

however, art is wholly integrated in the socio-cultural norms of ethnic groups in nations

across the continent; in fact, culture is a holistic part of art and vice versa. Teaero (2002)

further stresses on the threats haunting this pattern, this shrewd manifestation and dictation of

what he dubbed ‘eurocentricism’ in the African artistic expression when he states:

There is a salient need for newer ways of expressing the African traditional ideologies

and worldviews in a relevant and updated contemporary language for the purpose of

preserving, establishing, and empathically communicating the continent’s cultural identity

and ideals. It is also necessary for this ideological approach to be adapted to the evolving

twenty-first century art world. So far, this syndrome, what the researcher would refer to as an

As an important part of culture, art has always been

traditionally conceived, produced, used, distributed, and

critiqued by islanders from their ethnocentric

perspectives. Over the centuries alternative perspectives

– especially from a Eurocentric viewpoint– were

introduced, used and perpetuated through the school

system.(ibid.)

xv

“afro-centric renaissance in modern art”, has affected areas in the visual arts such as sculpture

and painting. On the contrary, however, there is an obvious conceptual dearth when it comes

to the aspect of employing the multimedia and, more specifically, video art as a medium for

expressing and projecting this concept.

The works of prominent African video artists like William Kentridge (South Africa)

exhibit a kind of universality that was not created to be interpreted from that cultural angle.

More so, they are actually not intended to do that. Perhaps this is because Video art, which is

an art that combines music, dance, performance, and computer graphics, shown on video, is

not only a relatively new genre in art, but is quite an alien concept in Africa unlike the other

aspects of arts that have definitive historical roots in the continent. Interestingly, it is a new

and exciting art and technological development that is fast becoming a huge consideration

fraught with endless innovative possibilities to both the artistic and academic worlds.

Kentridge’s works are primarily animations or animated drawings to be more precise.

Animation could be defined as:

Furniss further states:

the term implies to to creations on film, video, or

computers, and even to motion toys, which usually

consist of a series of drawings or photographs on paper

that are viewed with a mechanical device or by flipping

through a hand-held sequence of images (for example,

a pad of paper can be used to create an animated

flipbook of drawings). The term cartoon is sometimes

used to describe short animated works (under ten

minutes) that are humorous in nature. (Ibid)

motion pictures created by recording a series of still

images—drawings, objects, or people in various

positions of incremental movement—that when played

back no longer appear individually as static images but

combine to produce the illusion of unbroken motion.”

(Furniss, 2007).

xvi

Video art has generally undergone some conceptual evolution over the years, since its

introduction in the modern art scene around the late fifties and early sixties. Presently, an

avalanche of video art presentations have been created by artists and non-artists alike because

the medium itself is easy to obtain and manipulate by both professional and nonprofessionals

alike. What separates the video artist from the experimental video consumer is creativity; that

is the artist’s ability to manipulate the medium in order to address a whole range of issues in

its thematic content.

The integral Africa identity and worldview has been compromised in this new genre

of modern art. Unlike the other aspects of the visual arts, the challenges confronting video art

are connected with the technology that actually initiated it. Furthermore, the tendency of the

art to be abused due to the relatively easy accessibility of the technology by consumers and

the overabundance of easy-to-use editing software is another problematic issue. It is

important, since this art is still in its early stages when compared to the other arts, that the

African ideology be integrated into video art footages and themes, at least aesthetically.

There are very few video art footages in existence truly project the African ideologies and

motifs conceptually. In addition, it was Uche Okeke’s (1961) letter to the then president,

Nnamdi Azikiwe, which stoked the embers that later flared up the radical development of the

natural synthesis philosophy in Nsukka years later. The content of the letter reads:

I believe that it is only through the acceptance of

‘natural synthesis’ that the conflicts of the

contemporary African mind must be resolved…the

African artist must live in his culture and express or

interprete the yearnings of his society. He must not live

in an ivory tower (Okeke, 1961).

xvii

Uche Okeke was not just the leader and founding member of the Art Society

(popularly known as ‘Zaria Rebels’) that was formed in 1958, reputed for their propagation

of the Natural synthesis ideology, he also played a significant role in its development. The

Natural Synthesis ideology, as the name implies, involved ‘the acceptance of much of

European media and technique (though not barring experimentation with these)’ and the

development of styles and content close to the students’ Nigerian experience, whether it be

their own cultural tradition, that of other Nigerian cultures, or current Nigerian life’

(Ottenberg, 1997). Ottenberg, in citing Okeke’s 1960 speech to fellow members (which later

became its manifesto) states that this synthesis “was to be natural, unconscious, and unforced,

to come from the experience of the individual artists, including from their cultures” (ibid.)

The project is an investigation and creative exploration of the bridge that connects the

possibilities this new form of art offers with the integral creative tenets of indigenous

concepts in order to initiate a new artistic trans-cultural paradigm. The videos will involve

interpreting selected proverbs in staged and animated footages, and will also exhibit a sort of

aesthetic visual conundrum that is both poetic and surrealistic. The motifs and sketches will

be animated and sometimes interfaced with the abstract motion backgrounds in most of these

videos. All of these will relate to the general idea of the respective concepts. The visual

effects will not be entirely subjected to software manipulation alone; other creative strategies

and mediums will be employed if they are appropriate in ensuring a creative expression of the

video art. The project will be deliberately streamlined to accommodate motifs and ideas that

are indigenous to the Igbo (that is the uli and nsibidi motif), because of the patterns and

symbols inherent in them that are somewhat unanimous and relatively easier to access.

xviii

Statement of the Problem

Although there is an impressive display of dynamism in terms of video art concepts

shown by notable video artists in Africa, Europe and the rest of the globe, there is still an

aspect that has not been extensively explored or addressed in the aesthetic aspect of the

footages. The African socio-cultural identity, for instance, has been lost or ignored entirely in

these conceptual outbursts.

xix

There is therefore a need for diversities in artistic expression that individualizes the

African artists’ video concepts in a socio-cultural context, hence establishing a plausible and

effective platform for their respective projection.

Objectives of the Study

The objective of the research is to investigate the following issues:

To synthesize indigenous motifs and ideas into created video art footages in order to

arrive at themes that reveal socio-cultural ideologies. This would be achieved through

drawings, digital adaptation of the motifs to video footages and animations via appropriate

video and animation software alongside other relevant media hardware like HD cameras and

green screen props

To creatively employ innovative techniques that will bring out interesting results, as

well as approaches that reflect the African socio-cultural identity. Most of the concepts will

be captured chance occurrences and selected reference footages with socio-cultural allusions,

all of which will be digitally manipulated

To creatively manipulate the themes of video art footages in order to address issues

from a socio-cultural perspective. As earlier stated, the researcher will use video editing

software like Adobe Aftereffect, Pinnacle, Adobe Premier, Corel Video Studio to achieve

this. The researcher will also adopt a strategic process which will involve a workflow; that is

using the software that will best enhance an effect rather than wholly concentrating on one

xx

To examine the challenges or factors that have restricted and discouraged African

artists from exploring video art from this socio-cultural point of view and recommend

strategies in addressing this.

Significance of the Study

This study is significant because it will ensure that the African identity is not lost in

the growth and evolution of the expressive content of video art for subsequent African video

artists engaged in the medium. Ultimately, since video art is an aspect of visual

communication, it will introduce and further enhance the concept of hybridity with

indigenous designs, which will consequently inspire graphic designers to explore that

relatively uncharted area.

This study will also help to situate the African indigenous motif and values in the

history of the art for future reference and provide avenues for further research in this area.

Finally, it will add to written literature in the area of visual communication.

Scope of the Study

This research will focus on the aspect of video art that deals with capturing of staged

or chance performances that are in consonance with a specific theme. Also, other approaches

such as animation and installation video art will be explored. These strategic approaches are

necessary since the emphasis is on integrating socio-cultural idioms, like uli and nsibidi

motifs for example, into the fabric of the themes, and not using the technology itself as a tool

to achieve this, which on the long run will produce contradictory results.

Limitations

xxi

In the course of executing this project, the researcher encountered some challenges

that somewhat threatened the achievement of its stipulated aims and objectives.

Time factor is one that posed one of the greatest challenges during the course of

completing this research. Making of standard animations requires time and usually teamwork.

This is because of the enormous number of storyboards sketches that are meant to capture

each frame, as well as other aspects like sound effects and the like. The making of standard

animations usually require departments that are created to handle each of these aspects

effectively under a stipulated time frame and budget.

The high cost involved in successfully executing this project to its optimum was also

another limitation. Many of the hardware and software to be used to arrive at some interesting

and highly professional effects were very expensive and sometimes quite hard to find. The

researcher had to make do with downloaded trial versions, which had limited functions and

time usage.

Research Methodology

The collection of data for this research was through primary and secondary sources.

The primary sources involved fieldwork. The equipment used for the fieldwork include

writing pads, sketch pads and multimedia materials like ipads and tablets.

Data was also collected through secondary sources. The Nnamdi Azikiwe Library of

the University of Nigeria, Departmental library and the library at the Centre for

Contemporary art (CCA), Yaba, Lagos played important roles in this sense. Most of the data

were sourced from the books, theses, journals, magazines, articles and catalogues retrieved

from these libraries. In addition, the internet was necessary because it enabled the researcher

gain access to significant information from very rare books that would have been virtually

xxii

impossible to reach in Nigerian libraries. Data that involved video interviews and video art

footages from notable artists, retrieved from social media and sites like Youtube, were made

possible because of the internet.

Five major approaches were also adopted in the data analysis. They include aesthetic,

functional, historical, stylistic, and iconographic methods. The rationale behind the adoption

of these approaches is significant and relevant because of the following reasons:

The aesthetic approach was necessary in order to examine the quality of the

compositions in the video footages and animations based on its effectiveness in inducing a

pleasing visual appeal; the functional approach was used to ascertain the importance of

integrating ingenious motifs into video art concepts and animations; the stylistic approach for

analyzing the nature of used materials and their various techniques and distribution patterns;

and the iconographic approach for discussing the meanings associated with the symbols and

grabbed stills of the videos and animations.

Organisation

The research report has been structured into seven chapters. The first chapter

introduces the research and addresses the background, objective, significance, scope of the

study, as well as the methodology among others. The literature relevant to the research will

be reviewed in Chapter 2, while in chapter three the socio-cultural significance of the selected

motifs will be evaluated within the context of Nigerian modern art. Chapter 4 will be a

review of some Nigerian video artists who have made some invaluable contributions to the

development of the art in Nigeria. In chapter five, the methodological and technical approach

xxiii

for the execution of the video art concepts. The themes of the concepts will be discussed in

the sixth chapter, while the research will be concluded in the seventh.

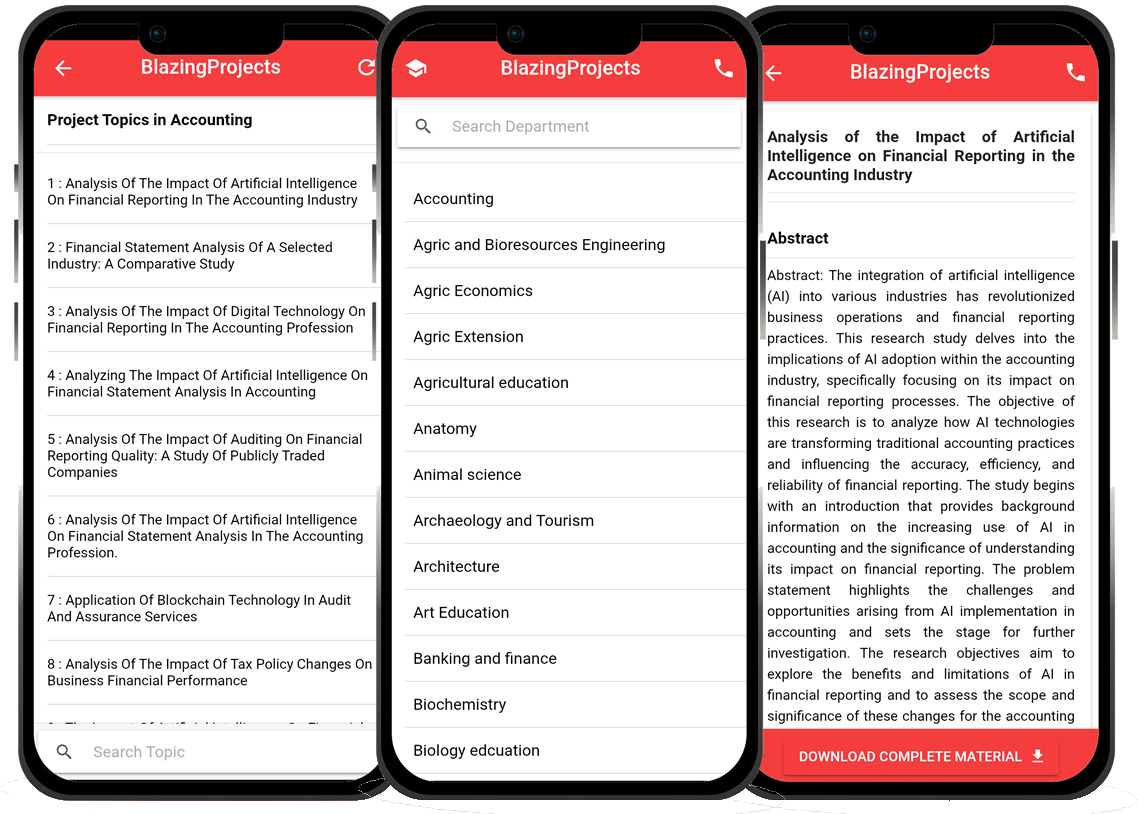

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional and Digital Painting Techniques in Contemp...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional and Digital Painting Techniques in Contemporary Art" delves into the dynamic relationshi...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Tools in Contem...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Tools in Contemporary Art Practice" aims to investigate the d...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Techniques and Modern Technology in Fine A...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Techniques and Modern Technology in Fine Art Creation" aims to investigate how the integ...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Technology in C...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Technology in Contemporary Art" aims to investigate the dynam...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional and Digital Art Techniques in Contemporary...

The research project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional and Digital Art Techniques in Contemporary Artworks" aims to investigate how th...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Technology in C...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Technology in Contemporary Art" aims to investigate the dynam...

The Intersection of Traditional and Digital Art Techniques in Contemporary Design...

The research project titled "The Intersection of Traditional and Digital Art Techniques in Contemporary Design" aims to investigate the integration of...

The Influence of Modern Technology on Traditional Artistic Techniques in Fine and Ap...

The project titled "The Influence of Modern Technology on Traditional Artistic Techniques in Fine and Applied Arts" aims to investigate the impact of ...

Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Media in Contem...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Traditional Art Techniques and Digital Media in Contemporary Art Creation" aims to investigate the d...