A Case Study of Primary Healthcare Services in Isu, Nigeria

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Primary Healthcare Services2.2 Historical Perspectives

2.3 Current Trends in Primary Healthcare

2.4 Importance of Primary Healthcare

2.5 Challenges in Primary Healthcare Services

2.6 Innovations in Primary Healthcare

2.7 Global Best Practices

2.8 Policies and Regulations

2.9 Technology in Primary Healthcare

2.10 Future Directions

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Data Collection Methods

3.3 Sampling Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Research Limitations

3.7 Research Validity and Reliability

3.8 Research Variables

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Findings4.2 Demographic Analysis

4.3 Service Utilization Patterns

4.4 Patient Feedback and Satisfaction

4.5 Healthcare Provider Perspectives

4.6 Comparison with National Standards

4.7 Recommendations for Improvement

4.8 Implications for Policy and Practice

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Recommendations for Future Research

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Contribution to Knowledge

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

Access to primary medical care and prevention services in Nigeria is limited, especially in rural areas, despite national and international efforts to improve health service delivery. Using a conceptual framework developed by Penchansky and Thomas, this case study explored the perceptions of community residents and healthcare providers regarding residents’ access to primary healthcare services in the rural area of Isu. Using a community-based research approach, semistructured interviews and focus groups were conducted with 27 participants, including government healthcare administrators, nurses and midwives, traditional healers, and residents. Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7- step method for qualitative data analysis. Key findings included that (a) healthcare is focused on children and pregnant women; (b) healthcare is largely ineffective because of insufficient funding, misguided leadership, poor system infrastructure, and facility neglect; (c) residents lack knowledge of and confidence in available primary healthcare services; (d) residents regularly use traditional healers even though these healers are not recognized by local government administrators; and (e) residents can be valuable participants in community-based research. The potential for positive social change includes improved communication between local government, residents, and traditional healers, and improved access to healthcare for residents.

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND OF STUDY

Many countries have limited access to primary healthcare for residents (Rutherford et al., 2009; World Health Organization [WHO], 2008b). A combination of factors contributes to this condition, including sociodemographic characteristics of the population, lack of resources, challenges posed by the primary-care model, and government healthcare administrators’ failure to incorporate input from the community regarding healthcare needs (Higgs, Bayne, & Murphy, 2001; Uneke et al., 2009). As a result, many people suffer illnesses unnecessarily, and communities experience high mortality and morbidity rates from preventable causes (Irwin et al., 2006). This unfortunate situation is the case among many African countries (World Bank, 2011). Compared to other countries, African countries bear a greater burden of disease and death from preventable and terminal causes. In fact, 72% of all deaths in Africa are the result of communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria; respiratory infections; and complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Deaths due to these conditions total 27% for all other WHO regions combined (WHO, 2006). In addition, the WHO reported that 19 of the 20 countries with highest maternal mortality ratios worldwide are in Africa. Data from a 2009 report from the World Bank (2011) indicated that the prevalence of HIV among people ages 15–49 in sub-Saharan Africa is nearly seven times of that in other areas of the world (5.4% compared to 0.8%, respectively). Similarly, WHO (2006) reported that Africans account for 60% of global HIV/AIDS cases, 90% of the 300–500 million clinical cases of malaria that occur each year, and 2.4 million new cases of tuberculosis each year. As of 2003, infant mortality rates were reported to be 29% higher than in the 1960s (43% up from 14%; WHO, 2006). Lack of safe drinking water (58% of the population) and access to sanitation systems (36% of the population) contribute to these poor health outcomes (WHO, 2006). However, these poor health conditions also are due in part to the historical and current states of primary healthcare in Africa, and particularly in Nigeria (Asuzu, 2004; National Primary Health Care Development Agency, 2007; Tulsi Chanrai Foundation, 2007; WHO, 2008b).

Over the years, international attention has been drawn to the global issue of limited access to primary healthcare for many populations. The outcome of this attention has been the initiation of numerous efforts to change this condition and develop modern and effective healthcare systems focused on preventing diseases (McCarthy, 2002; United Nations Children Fund [UNICEF], 2008; United Nations Population Fund, 2010; Wang, 2007); reducing disparity in health care (Andaya, 2009; Cueto, 2004; Gofin & Gofin, 2005; Latridis, 1990; Negin, Roberts, & Lingam, 2010; WHO, 1946); improving access to healthcare (Bourne, Keck, & Reed, 2006; Dresang, Brebrick, Murray, Shallue, & Sullivan-Vedder, 2005; WHO Country Office for India [COI], 2008); promoting active community participation in healthcare planning (International Conference on Primary Health Care [ICPHC], 1978; International Conference on Primary Health Care and Health Systems in Africa [ICPHCHSA], 2008; WHO, 1974); and promoting overall health and well-being (Hall & Taylor, 2003).

Efforts to this end have been effective in many nations (WHO, 2000b, 2008b). However, the early influence of Christian missionaries (Ityavyar, 1987; Kaseje, 2006), years of British imperialism leading to the amalgamation of Southern and Northern Nigeria (Ityavyar, 1987), Nigeria’s continued reliance on the ineffective British system of healthcare (Ityavyar, 1987), governmental inadequacy (African Development Bank, 2002; Asuzu & Ogundeji, 2007), and a 3-year civil war (Uche, 2008; Uchendu, 2007) have left the Federal Republic of Nigeria in a state of political, economic, and social unrest, unable to accommodate a governmental infrastructure to satisfy the diverse cultural needs of its people (Hargreaves, 2002). Particularly strained is the nation’s ability to provide access to effective healthcare for its growing population, especially in rural areas (African Development Bank, 2002). The sociodemographic characteristics of the population compound this condition (Labiran, Mafe, Onajole, & Lambo, 2008). Access to healthcare remains inadequate in Nigeria; however, there are very few data on community perceptions regarding this inadequate access to healthcare in rural Nigeria, and none in Isu.

1.2 Problem Statement

The residents of rural Nigeria lack access to adequate healthcare. One of the many factors contributing to this lack is the failure of the healthcare system to incorporate input from the community in planning and implementing services. As a result, there are very few reports of community input. There is a need to explore community perceptions regarding access to primary health care in the rural area of Isu. This problem is worthy of study because inability to access healthcare services is directly related to poor health outcomes (Cohen, Chavez, & Chehimi, 2007) such as those described in the introduction to this study.

1.3 Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of rural community residents and healthcare providers regarding residents’ access to primary healthcare services in Isu and to engage in community-based research to demonstrate its potential to promote resident access to healthcare services. Specifically, I gathered information regarding availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability; and acceptability of government healthcare services; characteristics of the healthcare system that hinder and that promote residents’ use of healthcare services; and the potential for community-based research to promote residents’ use of available healthcare services. By exploring these concepts through study participants’ perspectives, I generated data that may be used in constructing and distributing a ground-up model of a healthcare system that satisfies the expressed needs of the people of rural Isu. In addition, I have provided an example of community-based health access research—a relatively new area of research.

1.4 Conceptual Framework

Penchansky and Thomas’s (1981) model of healthcare access provided the framework that guided this study. According to Penchansky and Thomas, although access to healthcare is relevant to advancing health legislation and services, the concept has yet to be adequately defined; however, it is a condition that promotes inequality in healthcare distribution and widens the gap in health outcomes between the rich and poor, particularly evident between urban and rural populations. According to Penchansky and Thomas, access to healthcare does not refer generally to the use of a healthcare system or the factors that influence that use, nor is it measured by the health of the clients. Rather, access to healthcare refers to the compatibility between a person and the healthcare system available to them and is measured by factors that assess patient satisfaction or prevent them from using healthcare services. Penchansky and Thomas’s (1981) model of healthcare access provided a framework for developing my study. Specifically, I considered the five dimensions of access—availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and acceptability— while designing Research Questions 1 and 2 so that I could elicit responses related to all dimensions of access to healthcare in the community. I considered the dimension accommodation while designing Research Question 3 so that I could elicit responses related to the community-based research aspect of my study. In addition, I used the five dimensions of healthcare access to understand the barriers to healthcare access and the importance of overcoming those barriers as a means of improving rural health conditions. Also, in my literature review, I organized the presentation of the barriers to healthcare access according to the five dimensions. The model also provided an organizational structure for the presentation of my results. Finally, using Penchansky and Thomas’s (1981) model of access allowed me to present recommendations for improving healthcare access based on an accepted and proven conceptual framework. By exploring the conditions of healthcare access for the rural people of Isu through the lens of Penchansky and Thomas’s model of access, I gathered data that provide a deeper understanding of the impact of these dimensions of access to the health of Isu residents. Because of this understanding, I was better suited to present suggestions that may bring about changes in current government healthcare policies and practices and guide efforts to improve access to healthcare services for the residents of rural Isu

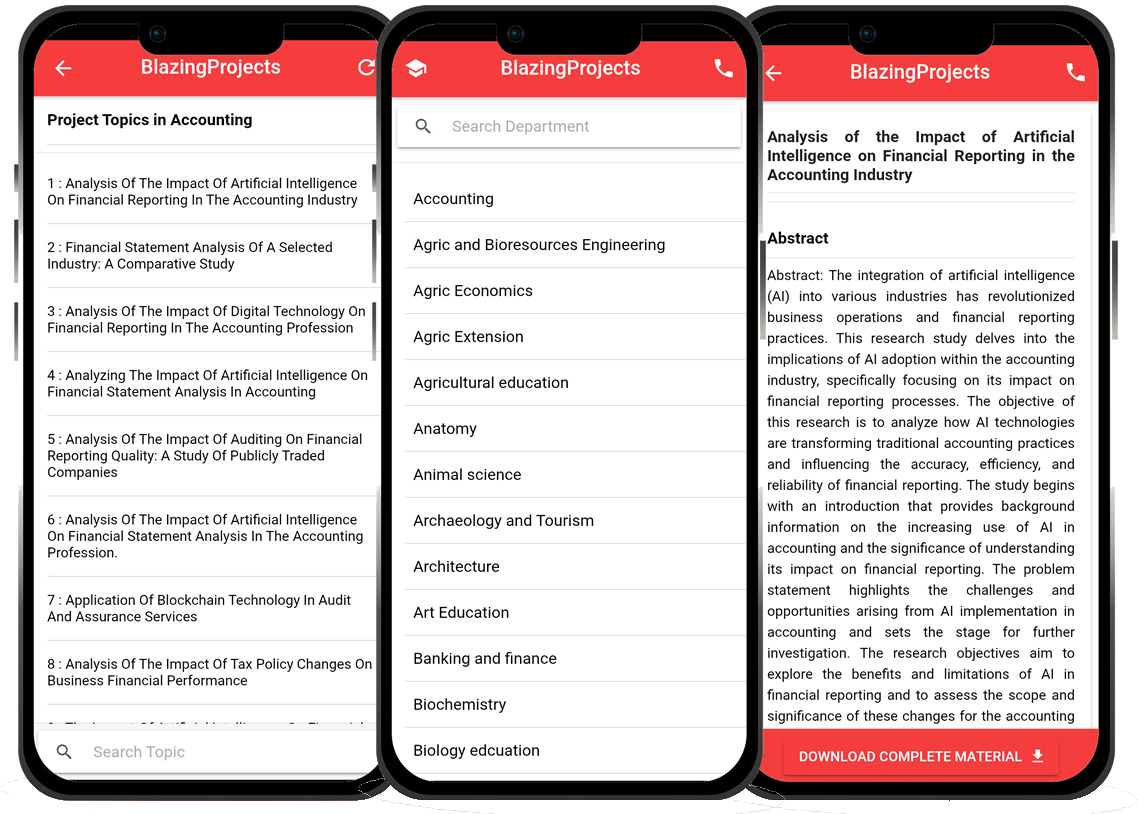

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

The Impact of Mental Health Education on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents...

The project topic, "The Impact of Mental Health Education on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents," aims to investigate the correlation between men...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Obese Ado...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Obese Adolescents," focuses on investigating the effect...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Sedentary...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Sedentary Young Adults," aims to investigate the effect...

The impact of mindfulness training on stress reduction in college athletes: A random...

Overview: The project focuses on investigating the impact of mindfulness training on stress reduction among college athletes through a randomized controlled tr...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Fitness in College ...

The research project titled "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Fitness in College Athletes" aims to investigate the eff...

The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress and Anxiety Levels in Colleg...

The project topic, "The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress and Anxiety Levels in College Students," aims to investigate the effective...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in College A...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in College Athletes," aims to investigate the effects of h...

The Impact of Mindfulness Practices on Stress Management and Academic Performance am...

The research project titled "The Impact of Mindfulness Practices on Stress Management and Academic Performance among College Students in Health and Physica...

The Impact of Technology on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents...

The research project titled "The Impact of Technology on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents" aims to investigate the relationship between technol...