Prevalence and correlates of stroke among older adults in Ghana: Evidence from the Study on Global AGEing and adult health (SAGE)

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Stroke2.2 Global Burden of Stroke

2.3 Risk Factors for Stroke

2.4 Stroke Management and Treatment

2.5 Impact of Stroke on Older Adults

2.6 Socioeconomic Factors and Stroke

2.7 Stroke Prevention Strategies

2.8 Technology and Stroke Rehabilitation

2.9 Psychological Effects of Stroke

2.10 Cultural Perspectives on Stroke

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Population and Sampling

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Data Analysis Techniques

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Research Instruments

3.7 Validity and Reliability

3.8 Limitations of Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants4.2 Prevalence of Stroke among Older Adults

4.3 Correlates of Stroke in Ghana

4.4 Health-seeking Behavior of Stroke Patients

4.5 Access to Healthcare Services

4.6 Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Stroke

4.7 Comparison with Global Data

4.8 Policy Implications

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Recommendations for Future Research

5.4 Implications for Public Health Policy

5.5 Contribution to Existing Literature

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

This study examines the prevalence and correlates of stroke among older adults in Ghana. This cross-sectional study retrieved data from Wave 1 of the World Health Organization (WHO) Survey on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) conducted between 2007 and 2008. The sample, comprising 4,279 respondents aged 50 years and above, was analysed using descriptive statistics, cross tabulations and Chi-Square tests, and a multivariable binary logistic regression. Respondents ranged in age from 50 to 114 years, with a median age of 62 years. Stroke prevalence was 2.6%, with the correlates being marital status, level of education, employment status, and living with hypertension or diabetes. The results showed that being separated/divorced, having primary and secondary education, being unemployed and living with hypertension and diabetes, significantly increased the odds of stroke prevalence in this population. The results suggest that interventions to reduce stroke prevalence and impact must be developed alongside interventions for hypertension, diabetes and sociodemographic/economic factors such as marital status, level of education, and employment status.

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND STUDY

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and the third leading cause of disability worldwide[1]. It is estimated that 15 million people suffer from stroke every year. Out of this number, about six million people die and another five million are left permanently disabled [2]. A total of 44 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) are lost to stroke every year and this is projected to increase to 61 million by 2020 [2]. The prevalence is projected to increase throughout the world because the number of persons aged 60 years and above is expected to more than double by 2050, and more than triple by 2100, increasing from 901 million in 2015 to 2.1billion in 2050 and 3.2 billion in 2100 [3].

In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), stroke incidence is increasing, and research has shown that stroke mortality will triple in Latin America, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa between 2002 and 2020 [4]. Community-based studies in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) show that stroke is the cause of 5–10% of all deaths, and this is partly because of inadequate health systems and increasing rates of hypertension [5]. Further, the impact of stroke is projected to go up in this region as a result of urbanization, poor socio-economic status and the change in the demographic structure of the population from young to an ageing population. By 2025, it is projected that about half of SSA’s populations will be living in urban areas and the number of people who are aged 60 years and above will more than double in countries like Ghana, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mozambique [6,7]. This projected demographic transition may increase stroke-induced disability in the region in the near future if serious measures are not put in place. Studies have shown that stroke is a major cause death and disability in Ghana [8]. Also, hypertension prevalence is already high in the country, with low rates of awareness, treatment and control [9-10]. This has serious implications for the burden of stroke unless urgent measures are taken to control hypertension [9]. The current situation shows that stroke is not on the list of priority health interventions outlined by Ghana's Ministry of Health and stroke burden has been under-researched and under-funded in Ghana [12].

Research showed that the risk factors of stroke include hypertension[13-16], diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiac disease [15-16], smoking [1,19-22], alcohol consumption [23-25], physical inactivity [26-29], obesity, regular meat consumption, low green leafy vegetable consumption, stress, and adding salt at the table [15-16]. In addition, sociodemographic/economic factors such as sex [6,30-33], age [1,34], level of education [35], wealth status [36-39] have been shown to be associated with stroke. Recent evidence by the Stroke Investigative Research and Evaluation Network (SIREN) multicenter case-control study showed the dominant modifiable risk factors of stroke in Ghana and Nigeria include hypertension, dyslipidemia, regular meat consumption, waist-to-hip ratio, diabetes, low green leafy vegetable consumption, stress, adding salt at the table, cardiac disease, physical inactivity and current cigarette smoking [16]. Nevertheless, the study provided limited information on the role of sociodemographic/economic factors on stroke prevalence and the findings cannot be generalized to the entire Ghana. Since social determinants of health (SDH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the fundamental drivers of these conditions [40], this indicates that their effects on stroke are context-specific and may provide important information on health disparities. To date, no study has examined the prevalence and correlates of stroke at the national level in the country, despite the importance of this evidence to drafting national guidelines and developing primary and secondary intervention strategies for the illness in Ghana. This study examines the prevalence and correlates of stroke in Ghana to address this important gap.

1.2 Data and methods

1.2.1 Study design

This cross-sectional study retrieved data from Wave 1 of the World Health Organization (WHO) survey on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) conducted between 2007 and 2008. The sample comprised 4,279 respondents aged 50 years and above.

1.2.2 Study area

The 2010 Population and Housing Census showed that Ghana has a population of 24,658,823, a larger proportion (51.2%) of whom are female[41]. The sex ratio is 95.2 males per 100 females. There are ten regions in the country. Of the ten regions in the country, the most populous is the Ashanti Region, made up of 19.4% of the total population; this is followed by Greater Accra Region (16.3%) with the least populated region being the Upper West Region (2.8%). With regard to the age structure, 38.3% of Ghana’s population is less than 15 years; 49.5% is 15–49 years, and; 12.2% is aged 50 years and above [41]. Further, a little over half of the population (50.9%) is living in urban areas [41]. More than 70% are Christians, 17.6% are Muslims, 5.2% are traditional worshippers and 5.3% do not have any religious affiliation. In terms of occupation, a larger proportion engages in agriculture-related activities. Specifically, 41.2% of the economically active population is skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; about 21% is also engaged as service and sales workers, while 15.2% are craft and related trade workers.

Ghana is a lower-middle income country with average per capita income of GH¢5,347(about US$1,353) [42]. The health system is structured to mainly treat infectious diseases [12]. The health care system in Ghana faces a lack of investment in health system and health workforce generally. Health spending as a percentage of GDP is 5.4% in 2013 [43], higher than the WHO recommendation of 5% . There are three teaching hospitals (Korle Bu in Accra, Komfo Anokye in Kumasi and Tamale Teaching hospital); nine regional hospitals; 96 government hospitals; and 1,106 health centres and clinics. In terms of the distribution of health professionals, there are 4,747 medical and dental practitioners, 1,832 physician assistants, 759, anaesthetics, 24,974 nurses, 1129 pharmacist and 41 health research officers. The doctor-population ratio was 1:11929 and the nurse to population ratio was 1:971 [41-45].

1.2.3 Sampling design

Ghana SAGE Wave 1 used a stratified, multistage cluster design that was based on the design for the World Health Survey [46] and presented a nationally representative sample. The primary sampling units were stratified by administrative region (Ashanti, Brong Ahafo, Central, Eastern, Greater Accra, Northern, Upper East, Upper West, Volta, and Western) and type of locality (urban/rural). Based on this, a total of 20 strata were developed [46,47]. From each of the strata, a total of 10–15 Enumeration Areas (EAs) were selected according to the population size. Household listings were done for each selected EA. Twenty households with persons aged 50 years and above, and four households with persons aged 18–49 years were then selected for interview [46]. All persons aged 50+ in ‘older’ households (households with at least one person aged 50-plus years) were invited to participate, whereas only one person was randomly selected in the ‘younger’ households (households with no person aged 50-plus years). Further, for those who were incapable of completing an interview for reasons of health or cognition, a proxy questionnaire was completed [46]. Standardized training in all aspects of the interview was provided to all interviewers. The questionnaires were translated into respective local languages, following a translation protocol, and modified to take into account the local context where needed [20]. The interview response rate was 86% [46].

1.2.3 Ethics statement

Ethical clearance and permission for the SAGE study was sought and approved by the Ethics Review Committee, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland and locally from Ethics Committee, University of Ghana Medical School, Accra, Ghana. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals.

1.3 MEASURES

1.3.1 Stroke prevalence

Stroke prevalence was based on self-report. The specific question asked during the survey was “Have you ever been told by a health professional that you have had a stroke?” Hence, the prevalence of stroke in this study was determined as the proportion of Ghanaians aged 50 years and above who had ever been told by a health professional that they have a stroke [46]. Self-reported diagnosis has been used to ascertain stroke prevalence in similar population-based studies in Africa [48] , Asia [49,50], Oceania [51,52], Europe [53,54], and North America [55-57]. These studies showed that self-reported diagnosis is a valid approach for estimating stroke prevalence and has high sensitivity and specificity values. During the data collection, respondents were provided with the definition of stroke. Stroke was described as a sudden and severe attack to the brain, which can cause permanent or temporary paralysis (inability to move, usually one side of the body) and loss of speech [58].

1.3.2 Physical activity

Physical activity was measured as the number of days respondents spent doing moderate-intensity activities including sports, fitness, or recreational leisure activities. This was re-categorized into three: physically inactive, partially active (those engaged in physical activities less than 3 times a week), and fully active (those who engaged in physical activities 3 or more times a week.

1.3.3 Smoking and alcohol consumption

Two questions were used to categorize smoking status. These included whether the respondent had ever smoked and if they currently smoked. These categories were re-grouped into non-smokers, previous smokers and current smokers. Those who responded ‘No’ to the two questions were referred to as ‘non-smokers’ while those who responded ‘Yes’ to whether they ever smoked and ‘No’ to whether they currently smoked were categorized as ‘previous-smokers’. Those who responded ‘yes’ to both questions were categorized as ‘current smokers’. Alcohol consumption was represented by three categories: non-drinkers (those who had ‘never’ consumed alcohol), occasional drinkers (those who had taken alcohol ‘once in a while’), and; regular drinkers (those who take alcohol ‘all the time’).

1.3.4 Body mass index

BMI was categorized according to WHO criteria (34): BMI < 18.5 (underweight), BMI = 18.5–24.99 (normal weight), BMI = 25–29.99 (overweight), and BMI ≥ 30 (obese).

1.3.5 Comorbidities

The comorbidities examined in this study were diabetes and hypertension. Respondents who had been diagnosed with hypertension by a health professional, and/or had the average of three blood pressure (BP) measurements to be systolic ≥140mm Hg, and/or diastolic BP of ≥ 90mm Hg, or were on antihypertensive medications, were regarded as living with hypertension. Diabetes prevalence was measured on a self-reported diagnosis by a health professional or use of insulin or other blood sugar lowering medications.

1.3.6 Other independent variables

The other independent variables included in this study were sex, age, place of residence, marital status, level of education, wealth status, religion, employment status and ethnicity.

1.4 DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics such as frequency distributions and median were used to describe the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the respondents, lifestyle factors, and comorbid conditions. At the bivariate level, cross tabulations and Chi-Square tests were used to determine the variation in stroke prevalence by socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors and comorbid conditions. Further, a multivariable binary logistic regression was used to examine correlates of stroke prevalence in Ghana and the alpha level for statistical significance was set at 0.05. At the multivariable analyses, the reference categories were theoretically selected based on what existing literature has shown. For instance, research shows that stroke prevalence is relatively higher among males compared to females; hence, we made the female gender the reference category in the multivariable analysis. Further, since the WHO SAGE used a stratified, multistage cluster sampling, appropriate sampling weights were applied before the analysis was done to adjust for the survey design. We also tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance; the outcomes indicate that there was no high intercorrelations among the variables (SI Table).

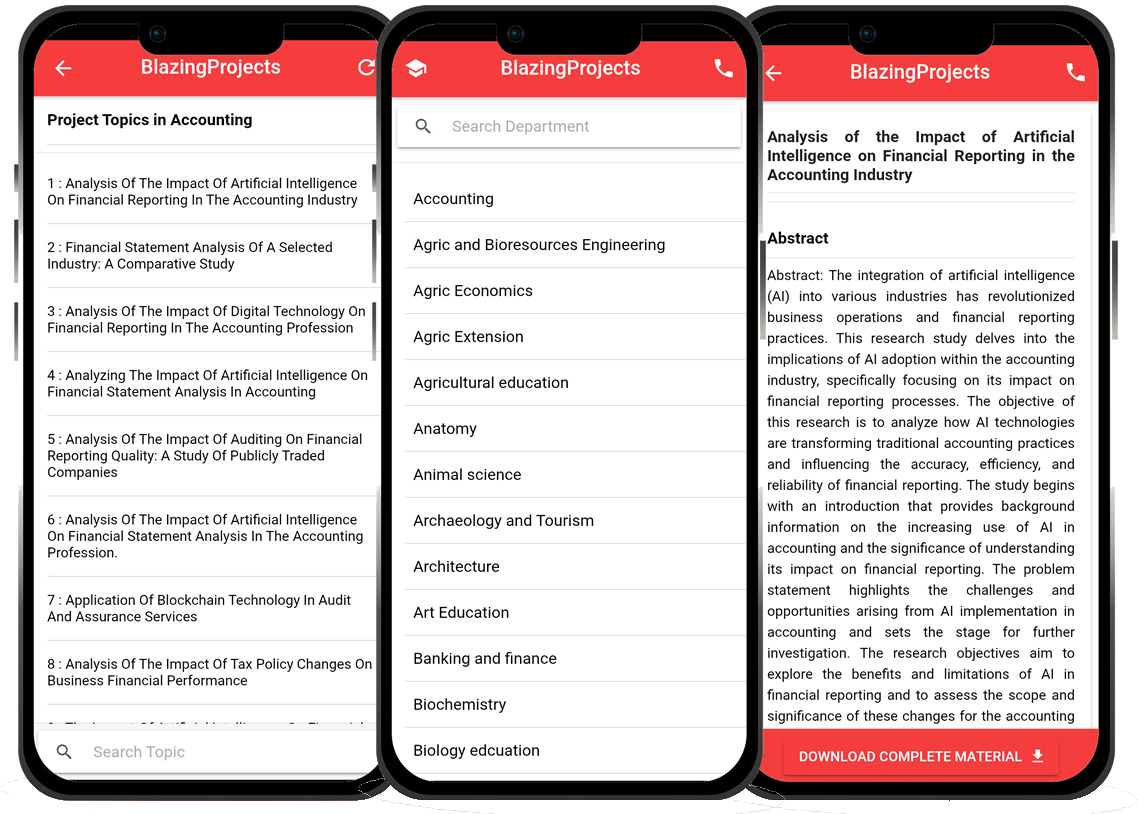

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

The Impact of Mental Health Education on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents...

The project topic, "The Impact of Mental Health Education on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents," aims to investigate the correlation between men...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Obese Ado...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Obese Adolescents," focuses on investigating the effect...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Sedentary...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in Sedentary Young Adults," aims to investigate the effect...

The impact of mindfulness training on stress reduction in college athletes: A random...

Overview: The project focuses on investigating the impact of mindfulness training on stress reduction among college athletes through a randomized controlled tr...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Fitness in College ...

The research project titled "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Fitness in College Athletes" aims to investigate the eff...

The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress and Anxiety Levels in Colleg...

The project topic, "The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress and Anxiety Levels in College Students," aims to investigate the effective...

The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in College A...

The project topic, "The Impact of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Health in College Athletes," aims to investigate the effects of h...

The Impact of Mindfulness Practices on Stress Management and Academic Performance am...

The research project titled "The Impact of Mindfulness Practices on Stress Management and Academic Performance among College Students in Health and Physica...

The Impact of Technology on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents...

The research project titled "The Impact of Technology on Physical Activity Levels in Adolescents" aims to investigate the relationship between technol...