Serum sodium concentration in sickle cell patient

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Serum Sodium Concentration2.2 Relationship between Sickle Cell Disease and Serum Sodium Concentration

2.3 Impact of Abnormal Sodium Levels on Sickle Cell Patients

2.4 Previous Studies on Serum Sodium Concentration in Sickle Cell Patients

2.5 Factors Affecting Serum Sodium Levels

2.6 Management of Sodium Imbalance in Sickle Cell Disease

2.7 Importance of Monitoring Serum Sodium in Sickle Cell Patients

2.8 Technologies for Measuring Serum Sodium Concentration

2.9 Current Guidelines for Sodium Management in Sickle Cell Disease

2.10 Future Research Directions in Serum Sodium Concentration and Sickle Cell Disease

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Selection of Participants

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Instruments for Data Collection

3.5 Data Analysis Techniques

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Pilot Study

3.8 Research Limitations

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Analysis of Serum Sodium Concentration in Sickle Cell Patients

4.3 Comparison of Sodium Levels in Different Sickle Cell Genotypes

4.4 Relationship between Serum Sodium and Disease Severity

4.5 Impact of Treatment on Serum Sodium Levels

4.6 Discussion on Factors Influencing Serum Sodium Concentration

4.7 Interpretation of Statistical Data

4.8 Implications of Findings for Clinical Practice

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Research Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Recommendations for Future Research

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Contribution to the Field

Project Abstract

AbstractSickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder that affects millions of individuals worldwide. Patients with SCD often experience a variety of complications, including electrolyte imbalances. Serum sodium concentration is an important electrolyte that plays a crucial role in maintaining the body's fluid balance and is essential for proper nerve and muscle function. This study aimed to investigate the serum sodium concentration in sickle cell patients and its correlation with disease severity and clinical outcomes. A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify relevant studies on serum sodium concentration in sickle cell patients. The search included databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, using keywords related to sickle cell disease, serum sodium, electrolyte imbalance, and clinical outcomes. Studies that reported on serum sodium levels in sickle cell patients and their association with disease severity, complications, and mortality were included in the review. The findings from the literature review revealed that sickle cell patients often exhibit lower serum sodium levels compared to individuals without the disease. Several factors were identified that could contribute to the dysregulation of sodium balance in SCD, including dehydration, vaso-occlusive crises, and renal dysfunction. Lower serum sodium levels were associated with increased disease severity, higher rates of hospitalizations, and a greater risk of complications such as acute chest syndrome and stroke. Furthermore, the review highlighted the importance of monitoring serum sodium levels in sickle cell patients as part of routine clinical care. Regular assessment of electrolyte imbalances, including sodium, can help healthcare providers identify patients at risk of complications and implement appropriate interventions to maintain electrolyte balance and improve clinical outcomes. In conclusion, serum sodium concentration is a critical parameter that warrants attention in the management of sickle cell disease. Monitoring and maintaining optimal sodium levels in these patients may help reduce the risk of complications and improve overall health outcomes. Further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying sodium dysregulation in sickle cell disease and to develop targeted interventions to address this issue effectively.

Project Overview

INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited disorders of the beta-hemoglobin chain. Normal hemoglobin has 3 different types of hemoglobin – hemoglobin A, A2, and F. Hemoglobin S in sickle cell disease contains an abnormal beta globin chain encoded by a substitution of valine for glutamic acid on chromosome 11 (Bunn,2007). This is an autosomal recessive disorder. Sickle cell disease refers to a specific genotype in which a person inherits one copy of the HbS gene and another gene coding for a qualitatively or quantitatively abnormal beta globin chain. Sickle cell anemia (HbSS) refers to patients who are homozygous for the HbS gene, while heterozygous forms may pair HbS with genes coding for other types of abnormal hemoglobin such as hemoglobin C, an autosomal recessive mutation which substitutes lysine for glutamic acid. In addition, persons can inherit a combination of HbS and β-thalassemia. The β-thalassemias represent an autosomal recessive disorder with reduced production or absence of β-globin chains resulting in anemia. Other genotype pairs include HbSD, HbSO-Arab and HbSE (Meremiku, 2008).

Sickle hemoglobin in these disorders cause affected red blood cells to polymerize under conditions of low oxygen tension resulting in the characteristic sickle shape. Normal red cells live about 120 days in the blood stream but sickled red cells die after about 10 – 20 days. Because they cannot be replaced fast enough, the blood is chronically short of red blood cells, a condition called anaemia. Aggregation of sickle cells in the microcirculation from inflammation, endothelial abnormalities, and thrombophilia lead to ischemia in end organs and tissues distal to the blockage (Hayes, 2004).

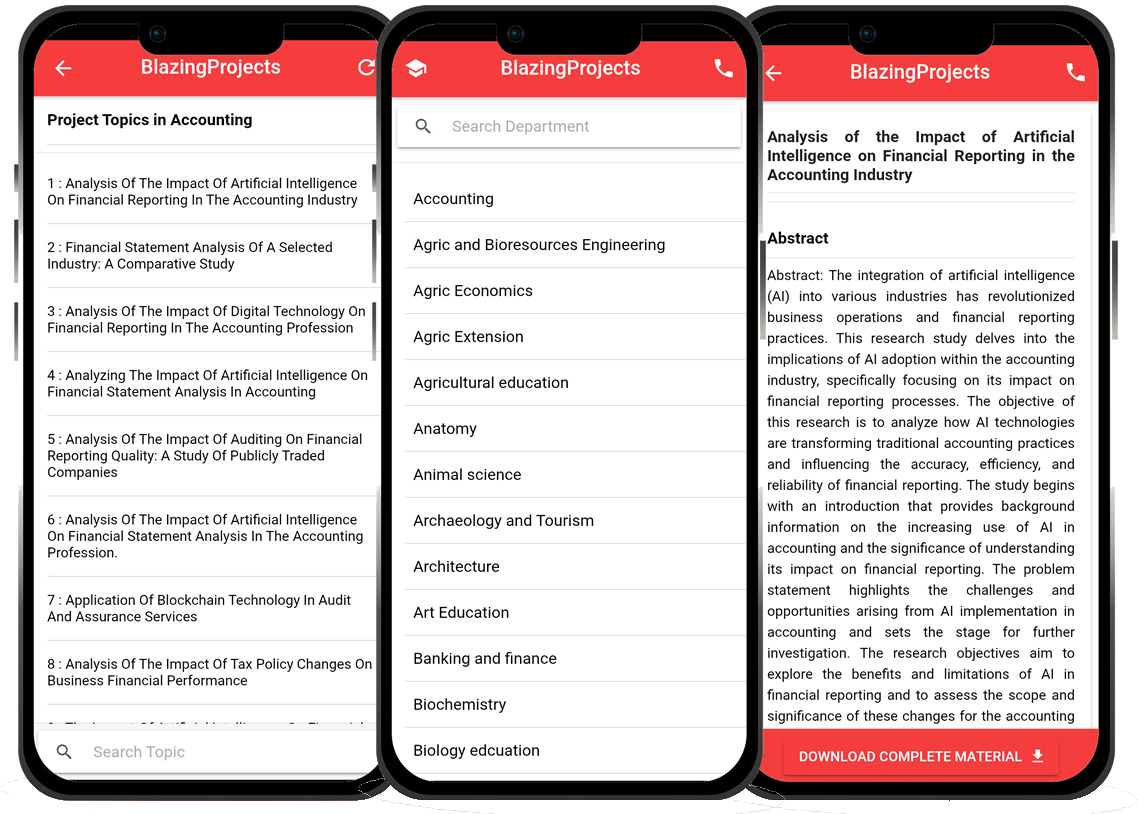

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Assessing the effectiveness of multimedia simulations in teaching cellular respirat...

...

Exploring the impact of outdoor fieldwork on student attitudes towards biology....

...

Investigating the use of concept mapping in teaching biological classification....

...

Analyzing the influence of cultural diversity on biology education....

...

Assessing the impact of cooperative learning on student understanding of genetics....

...

Investigating the effectiveness of online quizzes in promoting biology knowledge re...

...

Exploring the use of storytelling in teaching ecological concepts....

...

Analyzing the impact of teacher-student relationships on student achievement in biol...

...

Investigating the role of metacognitive strategies in biology learning....

...