Development of sculpture forfunctionality: an exploration with terracotta in the landscape

Table Of Contents

<p> </p><p>Title page .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. i<br>Declaration .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ii<br>Certification .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. iii<br>Dedication .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. iv<br>Acknowledgement .. .. .. .. .. .. .. v<br>Abstract .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. vii<br>Table of contents .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. viii<br>List of plates .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. x<br>

Chapter 1

: BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY<br>1.1 Introduction… .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1<br>1.2 Statement of the Problem.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5<br>1.3 Objectives of the Study.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6<br>1.4 Scope and Delimitation of the Study.. .. .. .. .. 6<br>1.5 Justification of the study.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6<br>1.6 Significance of the study.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6<br>Chapter 2

: REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE AND WORKS<br>2.1 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. 7<br>2.2 Review of Relevant Literature .. .. .. .. .. 7<br>2.3 Review of related works.. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18<br>Chapter 3

: METHODOLOGY<br>3.1 Introduction.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 47<br>ix<br>3.2 Procedure .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 47<br>Chapter 4

: CATALOGUE OF STUDIO WORKS<br>4.1 Catalogue of Studio Works .. .. .. .. .. .. 54<br>Chapter 5

:<br>FINDINGS, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS<br>5.1 Prospects .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 67<br>5.2 Problems .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 67<br>5.3 Summary .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 68<br>5.4 Conclusion .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 69<br>5.5 Recommendations .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 69<br>References .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 71<br>x</p><p> </p> <br><p></p>Project Abstract

The history of sculpture from time reveals the use of varied materials as well as its

utility for a multitude of functions; amidst this too is the contentious issue of the

varied spaces in which sculpture is placed. However there was a glaring trend

since the prehistoric period of the close affinity of sculpture with architectural

spaces which seemed to have placed a kind of limitation on the freedom of

sculptors as well as the choice of space for sculpture. On the contemporary scene,

while it is known that sculptors in Europe and America have been able to liberalise

the choice of spaces exploring with a wider range of industrial methods and media,

there continued to be a noticeable trend, within the Nigeria landscape, that

sculptures continued to be entwined within architectural spaces. Worst still,

terracotta as a material for sculpture has continued to be used only for works

meant for the four walls of archy spaces, this is despite the use of more fragile

materials, like glass for sculpture in the open landscape. The objective of this

project was, therefore, to produce terracotta sculpture for the landscape in public

spaces, to be touched, walked through or stayed in temporarily. Essentially relying

on real models, diagrams and illustrations adapted to suit the intended functional

purposes, the method used was largely based on empirical observation and studio

experiment. While the making of large colossal piece of terracotta meant for

public traffic proved an arduous task in building and firing, the experienced

afforded a stimulating line of rendition and opened a new vista in the acceptance

of the degradation that affects terracotta sculptures as they get eroded by both the

inevitable natural and artificial agents of enthrophic dilapidation.

Project Overview

BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

1.1 Introduction

Sculpture has a history of functionality as well as that of the politics of the

space it occupies or its environment; two options are clearly discernible: the

interior space and the exterior landscape. Within the interior, it may be enclosed in

the inside spaces of buildings, or in dingy rooms of an underground burial

chamber or better still, meant to be concealed in the body space of a carrier who

tucked it away under the dress. For the open-air landscape it may mean sculpture

of the open arena in the public spaces, site-specific locations, and contextual

spaces.

An initial reference to the function and functionality of the many ancient

flint stone implements of the pre-historic man puts the story of sculpture in the

right perspective. To tell the same story of contemporary sculptures in the open

landscape, one needs to mention the protracted romance between sculpture and

architecture since the period of the pre-historic cave dwellings. According to

Janson (1973), the first known pictures and sculptures were done on walls of caves

by people who lived in caves. The functions of such etched or engraved

sculptures, according to Gilbert and McCater (1988) were “to exert control over

the forces of nature”, the environment where the works were placed and the

restriction of such placement to the interior being in line with their condition of

living, availability of the material surface and function. Clottes (2002) agrees that

2

there were, probably, no better place than the walls of their shelters for such

renditions.

However, with time human activities became more complex, the tempo of

religious activities equally increased with the attending ritual practices and

sacrifices, hence the choice of sculpture’s location or environment in respect to its

functions and functionality depended more on a number of factors. For example, it

became apparent to embellish open spaces like tombs and temple- adjoining –

spaces with much larger colossal pieces that were seen as the dawn of open air

sculptures. Savage (1969) and Aldred (1980) agree on the sphinx at Giza built

around 2550 BC and the Japanese bronze Budha done around the first century

A.D. as examples respectively.

Answers to the question as to why sculpture has been so long entwined

with architecture may be found in sculpture’s close association with the fabric of

the built environment which has taken it with much difficulty to shake off that

deep rooted connection. Carless and Brewster (1959) report that sculpture and

architecture have always been allied. World Book Encyclopaedia (2002) opines

that “stone masons’ skills approached that of the sculptor” simply because similar

materials are used in both. Dmoschowski (1990), from an architect’s perspective,

sees sculpture and architecture as “closely knitted”. Coldstream (1991) writes that

the distinction between the two was always blurred because it is really difficult to

isolate the moment at which sculpture emerged as specialisation and that “the

profession of stone carvers was rooted in the quarry and the lodge”.

3

From the above perspective, the history of the incidence of space, location,

site or environment of sculpture has been largely due to an array of influences.

Fagg and Plass (1966) agree that form follows functions and that those functions

which may be diverse have largely been responsible for where a sculpture is

placed and the arena in which sculpture inhabits. For example, personal objects as

“Akuaba” of Ghana and “Ere Ibeji” of Yoruba carvings are often meant to be

tucked in dresses where the bodily arena becomes their environments. In the same

vein, other sculptures of paraphernalia status, according to Ravenhill (1992),

surround the immediate environment of the body as dictated by their functions.

Curtis (1999) asserts that “subjects for commemoration suggested not only the

appropriate form of their monuments but also the site”. He states further that

doctors were put outside their hospitals, academics in universities and statues of

men action were erected to face the hustle and bustle of the city square. In the

contemporary scene, public role functions that took sculpture to such exterior open

spaces, traditional burial sites and modern cemeteries is not unconnected with

grave stones of the tombs of kings, the notables and the wealthy.

The demand for leisure in the modern times made sculpture to be more

accepted in leafy glades, parks and gardens and the philosophy of modernism

allowed sculptors to seek for more freedom from the overbearing influence of

architects. The ensuing parting of ways brought the cherished freedom to work

more in the open landscape. The advent of scientific discoveries, modern

techniques and rapid pace of life in 19th century, according to Arnason (1981),

4

brought an accompanying guarantee for the dissemination of new ideas and

achievements.

Deepwell (1995) on his own highlights the growing discontent for sculpture

“enslaved” within the confines of architectural setting or four walls for museum

oriented audiences. While utilising the principles of industrial production sculptors

have tried to “liberate” sculpture from the shaky union between it and architecture.

Hammercher (1969) reports that Ducham Villion advocated for sculpture that live

in the open air day light as “something different from sculpture suitable for

architecture and architectural setting’’. For Wezzel Couzin, one of his sculptures

literally escapes from the wall assigned to it and shoots out: instead of a wall

statue, the work became a statue for the entire structure.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the issue of the environment or space of

sculpture especially in the open landscape became a contentious issue. Kastner and

Wallis (1998) state that sculptors began to question the notion of sculptural

verticality and started responding to the horizontality of the land. Noguchi (1987)

describes such move by Isamu Noguchi with his “Sculpture To Be Seen From

Mars”. Henry Moore in Read (1965) on the Time life Building Sculpture states

that: “because a work is placed in the terrace and stands freely from the building it

could be, therefore, more individualistic and complete in its own right”

In addition, Coe (1978) opines that Eldred Dale, an American artist,

believed in the enrichment of sculpture for the open landscape such that the

physical world, as a lab, becomes the open air studio, galleries and museums for

5

monumental works in places like city squares, schools, centre of traffic, vast arid

land and to punctuate jungles.

Whether aesthetically, physically or otherwise, all works of arts in the open

landscape perform a kind of function or the other. The likes of the environmental

sculpture that is the focus of this research are meant for public outdoor spaces and

to be large enough for the viewer to enter and move about. These are terracotta

pieces which are designed for display in the outdoor environment in such places as

street lobbies, pedestrian malls, and open fields either as pass-through, temporary

shelters for momentary stoppages by passers-by and even domestic animals.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Amidst the wind of change as brought to the fore by sculptors in Europe

and America in line with philosophy of modernism, and with reference to the

perennial use of clay as a material by both Ceramists and Sculptors (Okpe, 2004),

this researcher is not aware of the same level of exploration with sculptures for the

landscape in the Nigerian scene hence most works have continued to be entwined

within arch spaces. Despite its inherent qualities, prolong history of use, its low

cost and commonality, terracotta sculptures continued to be made largely for the

interior spaces as this researcher is also not aware of its extensive use for such

functional sculpture meant for practical public embrace in the open landscape in

Nigeria. The problem of this research therefore is how can terracotta sculptures be

explored in the open landscape to such a level of functionality as for people to go

in, walk around and through.

6

1.3 Objectives of the Study

The main objective of this study is to explore the use of terracotta for

sculptures to be placed in the exterior public spaces while the other objective is to

create three dimensional terracotta sculptures for functionality as an ambience in

the public exterior spaces for practical utility.

1.4 Scope and Delimitation of the Study

This study is delimited in its scope to, primarily, the production of

sculptures for the open landscape using terracotta: the choice of the medium being

largely informed by its limited use for works meant for functionality as pass

through and temporary shelters outdoors.

1.5 Justification of the Study

The utter lack, absence or dearth of colossal or monumental terracotta

pieces for the public spaces in the open land space within Nigeria landscape forms

the basis of justification for this research. This is further strengthened by the fact

that the pieces are to be subjected to one form of public physical functionality or

the other.

1.6 Significance of the Study

Sculptures in open spaces in various media may have been done elsewhere

and especially in Nigeria. The bulk of the work of this research in an attempt to

stretch the context of the use of sculpture to such limit of functionality demanding

a public romance. This is in addition to bridging the yawning gap of such pieces in

a material like terracotta, an unusual phenomenon in the Nigerian landscape.

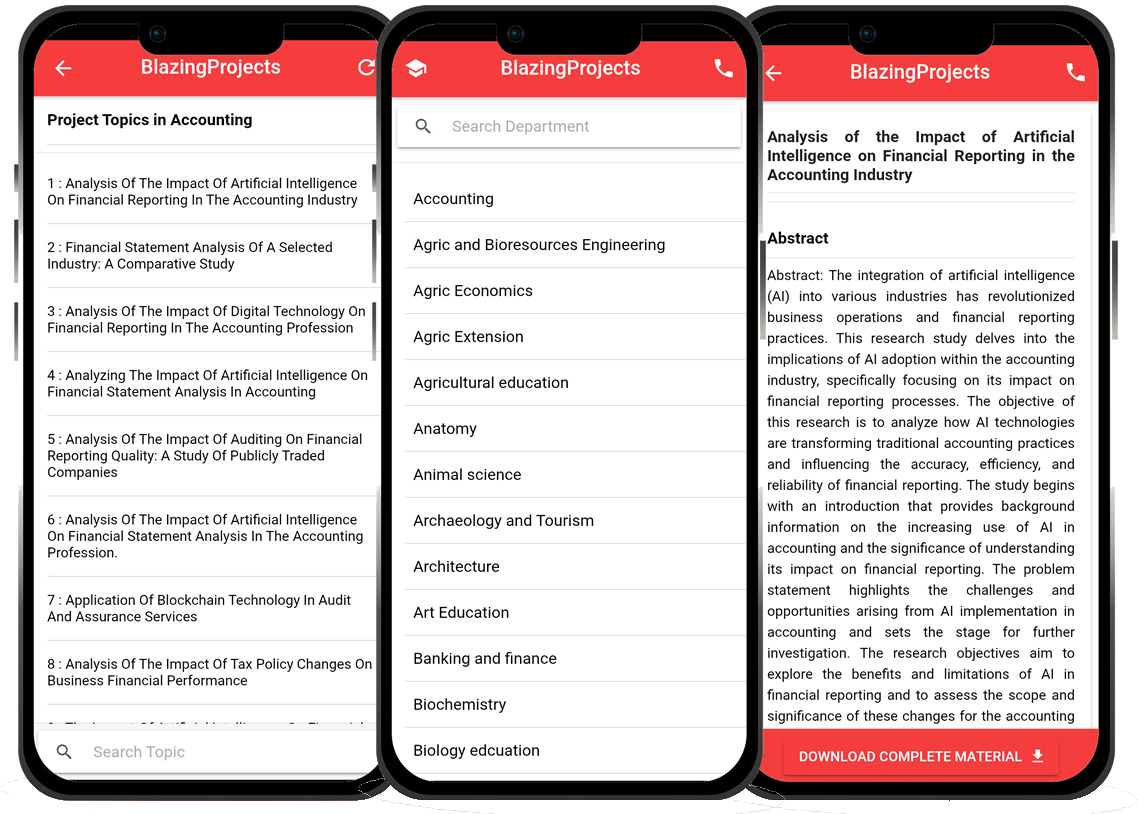

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Impact of Digital Art Platforms on Art Education in Secondary Schools...

The research project, "Exploring the Impact of Digital Art Platforms on Art Education in Secondary Schools," delves into the transformative effects of...

Exploring the Impact of Digital Technology on Art Education in Secondary Schools...

The research project titled "Exploring the Impact of Digital Technology on Art Education in Secondary Schools" aims to investigate the influence and i...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education...

The project, "Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education," aims to investigate the influence of virtual reality (VR) technolo...

Investigating the Impact of Digital Technologies on Creative Learning in Art Educati...

The project titled "Investigating the Impact of Digital Technologies on Creative Learning in Art Education" aims to explore how the integration of dig...

Exploring the Impact of Visual Arts Integration on Student Learning in Elementary Sc...

The project topic "Exploring the Impact of Visual Arts Integration on Student Learning in Elementary Schools" aims to investigate the effects of incor...

The Influence of Technology on Teaching Art in Secondary Schools...

The project topic "The Influence of Technology on Teaching Art in Secondary Schools" delves into the intersection of technology and art education in t...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education....

The project titled "Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education" aims to investigate the effects of incorporating virtual real...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education...

Overview: The integration of technology in education has revolutionized the traditional teaching and learning methods across various disciplines. In the realm ...

The Impact of Technology on Art Education: A Case Study of Virtual Reality in the Cl...

The Impact of Technology on Art Education: A Case Study of Virtual Reality in the Classroom Overview: Art education has always been a dynamic field that contin...