An analysis of unconventional materials used for art expression by nine (9) selected nigerian artists

Table Of Contents

<p> Title Page………………………………………………………………………..…i<br>Declaration ………………………………………………………………………..ii<br>Certification ………………………………………………………………………iii<br>Dedication ………………………………………………………………………….iv<br>Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………….v<br>Abstract …………………………………………………………………………….vi<br>Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………..vii<br>

Chapter ONE

: INTRODUCTION<br>Background to the Study ……………………………………………………………1<br>Statement of the Problem……………………………………………………………15<br>Aim and Objectives of the Study ……………………………………………………16<br>Research Question …………………………………………………………………..16<br>Significance of the Study ……………………………………………………………17<br>Justification of the Study ……………………………………………………………17<br>Significance of the Study ……………………………………………………………17<br>Scope of the Study …………………………………………………………………..18<br>vii<br>Chapter TWO

: LITERATURE REVIEW<br>Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………20<br>Review of Literature on Related Studies ……………………………………………..22<br>Chapter THREE

: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND PROCEDURE<br>Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………28<br>Sources of Data ………………………………………………………………………….28<br>Population of the Study…………………………………………………………………29<br>Sampling ……………………………………………………………………………….29<br>Research Instruments …………………………………………………………………..30<br>Theoretical Framework …………………………………………………………………30<br>Design Model ………………………………………………………………………………31<br>Chapter FOUR

: FIELD WORK DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION<br>Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………33<br>The Selected Artists and their works ……………………………………………………….34<br>Ayo Adewumi (b.1965) …………………………………………………………………..34<br>Ayo Aina (b.1969) …………………………………………………………………………44<br>Ikechukwu Francis Okoronkwo (b.1970) …………………………………………………55<br>Jerry Buhari (b.1959) ……………………………………………………………………..66<br>Mabel Onyekachi Chukwu (b.1975) …………………………………………………….76<br>viii<br>Ndidi Dike (b.1960) ……………………………………………………………………..86<br>Nkechi Nwosu Igbo (b.1973) ……………………………………………………………96<br>Nsikak Essien (b.1957) …………………………………………………………………105<br>Sussan Ogeyi Omagu (b.1973) …………………………………………………………114<br>Analyses of Works ………………………………………………………………………123<br>Motivation in Creating Art Works ………………………………………………………124<br>Interrogation of the courage in Art Creations ……………………………………………125<br>Thematic Concerns and Messages from the Works ……………………………………..129<br>Chapter FIVE

: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS<br>Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..142<br>Summary and Findings …………………………………………………………………143<br>Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………145<br>Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………146<br>Contribution to knowledge ………………………………………………………………148<br>Reference ………………………………………………………………………………..149<br>Appendix …………………………………………………………………………………153 <br></p>Project Abstract

Since the revolution earlier started with the emergence of the Renaissance in Europe, new

ideas of art creation, kept evolving as artists continued to show dissatisfaction with state-ofthe-art expression. The plethora of media for art expression spread beyond the boundaries of

Europe. More explorations and experiments kept intensifying, leading to discoveries and

inventions of other materials and techniques with the hope to present art forms that express

something better than previous creations. Different movements were formed in line with

their different ideologies. In the early 20th century, Western artists like Marcel Duchamp and

Pablo Picasso appropriated found objects as creative devices. People were shocked seeing

those kinds of art creation. The first and the second World Wars witnessed radical use of

waste in art expression. Transforming of waste and found objects into works of art not only

shows the boundless powers of human imagination, but also exposes the innate creative

potentials that such materials possess. In Africa, various artists like El Anatsui,

Dilomprizulike, Alex Nwokolo, among others, have critically engaged waste and found

objects as viable media for artistic expression. Groups like Bruce Onokbrapeya Foundation

(BOF), Art is Everywhere Project, among many, have organized seminars and workshops to

sensitize the public not only on the creative possibilities of unconventional materials, but

also on the use of found objects imbued with art works with peculiar aesthetics, which make

profound visual statements. The artists understudy, were individually motivated by nature

and their different models, but further acquired more skills and experiences through

explorations and experimentations. The choice of unconventional materials and the

techniques used by each of them for their art creations were marks of creative independence

attained by each of the artists. Most of their expressions were in the areas of paintings,

sculptures, installation arts, and mixed media exploration. Each of the works displays

exquisite expression, revels reinvention of new context. and ideation. Given the growing

global concerns on environmental degradation and climate change, the transformation of

waste and found objects into works of art imbued with new meaning is an important avenue

for having a sustainable environment. The artists derived different levels of satisfaction for

using the materials. This informed their courage and continuous creations in materials and

techniques that are unequaled. Based on the findings made after the analysis, one of the

major recommendations is the early exposition of students to the aesthetic potentials of

unconventional materials, preferable when they are still quite young. It is believed that they

will grow up to value the creative potentials inherent in the materials. Artists should always

seek out new challenges in order to task their creative skills, harness their uncertainty and

fuel their brilliant concepts.

Project Overview

INTRODUCTION

Background of the Study

Art expression in term of materials has experienced levels of changes as a result of the

revolution earlier started with the emergence of Renaissance Art in Europe. The rise of the

rich middle class, alongside people of means, supported scholarship. The initial method of

acquiring knowledge in art creation was through apprenticeship. Young aspiring artists

received the skills in the studios of established artists. Apprenticeship as a system faded out

with time. Schools being accepted as means of massive enlightenment started springing up

in different parts of Europe. Saxton (1981) notes that the first formal art school in the west

was established in 1562 in Florence, Italy, while in England, the Royal Academy was

established in 1768. By the eighteenth century, schools in Europe had increased to a

hundred. The author notes that irrespective of where the art school was located, the

emphasis was the need to stimulate the creativity of the individuals. The focus was the

development of the full imaginative potential of the aspiring artists by exposing them to a

wide range of media.

Explorations and experiments led to diversification of the media of expression. Colour as a

medium, for instance, with its different attractions to artists, occupied a commanding

position for the diversity in their individual expressions. The shades of colours in their

varieties were made to change and shift about in the quest by artists for greater dynamic

unity. Variety further offers different approaches in order to gain more satisfaction. The

desire for satisfaction was later extended to other media of expression. De la Croix and

Tansey (1980), having assessed the periodical changes, state thus:

2

For Europe, the nineteenth century was an age of radical change during

which the modern world took shape. In a world experiencing a population

explosion of unprecedented magnitude, revolution follows upon revolution,

punctuated by counter-revolution and conservative reactions … The

revolutionary shakeups of authority reverberate through the century,

carrying the hope of people for something newer, better, truer, and purer.

As search for fresh media and concepts to effect the change in expression was intensified,

Reid (1975), notes that some artists explored and experimented extensively and the outcome

of the explorations and experimentations was the exhibition of diversity on their works. For

instance, in 1786, one of the leading Neo-Classicist painters, John Zoffany, came out with a

completely different type of literary illustration titled ―Charles Macklin as Shylock‖, a

portrait study of an actor playing a part on the stage.

The range of art creation was expanding by the development of other more peculiar types of

art expression. By combining industrial and scientific subjects on one composition to

achieve the contrast effect of light, Joseph Wright of Derby‘s ―Experiment with the Air-Air

Pump‖ was a compelling art piece. In 1848, when Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed

by Holman Hunt and his colleagues, the author observes that the group felt dissatisfied with

the state of the art in England because it seemed to lack vigour, sincerity and seriousness.

This became obvious when the works were put in contrast with the quality of the art in Italy

and northern Europe before the time of Raphael. The artists attributed the weakness to

neglect of nature and over-dependence, instead, on academic conventions. To address this,

they initiated ―a child-like‖ reversion from existing schools to nature herself. The artists

displayed differing interests by evolving different media and techniques of art expression

which changed the face of art expression in England. This was as a result of Holman Hunt‘s

insistence on remarkable powers of observation and pictorial invention.

The emergence of Impressionists and the Post-Impressionists in the art scene witnessed the

exhibition of the most recent of the series of masterpieces of paintings from the thirteenth to

3

the nineteenth century. Their paintings, whose focus was to find a new truth, were derided,

hated or ignored purely on moral grounds. The artists deliberately evolved diversification

and innovation in the process of their art creation. This accelerated art in the way that is

comparable with the rate in the fields of science and technology. Cezanne, for example,

spent years working in isolation appropriating different media in order to reconcile his

perceptions with the relationships of touches of colour on the flat picture surface. The artist,

through experiment, understood that the appearance of objects change as the eye moves over

and around it. This was largely because of the media and techniques he devised to integrate

the picture-surface so that all the shapes on it were made to relate to one another, which

consequently led to Cubism, an abstract art of the century. Gauguin, another artist, turned

against the rationalism and materialism of his period and went to live in Tahiti, where he

was moved by the simplicity and mystery of the way of life of the peasants and natives. The

artist tried to find an equivalent to this in his diverse painting. Another artist who evolved

improvisations in his art production was Rodin. He strived to give his forms new freedom,

sometimes bridging them in space.

A group of painters (Henri Matisse, Andre Derain, and Albert Marquet, among many) came

together and staged an exhibition in 1905. The artists was named fauves (wild beasts)

because of their approaches. The painters rejected traditional rendering of three-dimensional

space defined by colours. They used vivid, non-naturalistic and exuberant media. Colours,

raw from the tubes, were applied and forms were aggressively manipulated to the point of

distortion. The work from Henri Matisse titled ―Woman with the Hat‖ is a typical example

of the characteristics of the works of the Fauvists. Their works displayed at an exhibition

were appalling to the viewers and were subjected to mockery and abuse at the time. Henri

Matisse developed an entirely new approach to art expression in terms of art materials and

4

techniques when he was ill. Different shapes of colours were cut from papers and coloured

in gouache. These were pasted on a ground by assistants under his watch. An example of

this is the work titled ―L‘Escargot‖, produced and exhibited in 1953.

In his study, Stokstad (1995) notes that Pablo Picasso joined a group of young writers and

artists, interested in progressive art and politics. He also gathered experiences from other

artists because of his frequent visits to their studios. In 1912 Pablo Picasso was preoccupied with creating works with more clearly-discernible materials. The approach led to

what was later known as ―Synthetic Cubism‖, particularly the work titled ―Glass and Bottle

of Suze‖, composed of separate elements pasted together. At the centre of the composition is

the combination of newsprint and construction arrangement of paper cut to suggest a tray or

round table upon which are glass and a bottle of liquor. The author observes that this

approach of art rendition was carried to the point of complete abstraction, although a few

allusions to objects still remained. Pablo Picasso‘s compositions started showing flat planes

being replaced by other flat materials. His focus was shifted to composing works with

machines and machine-made objects.

Cubism as a movement stimulated other similar movements. Prominent among these, was

Futurism, founded in Italy by a poet, Marinetti. Reid (1975), states that unlike other

previous movements, Futurism was propagandised in words, as well as in paintings and

sculpture materials. The artists of this movement created works with the sole aim of

destroying the art of the past which was seen as oppressive to the young artists, especially in

Italy. The Futurists hoped to substitute a new art based on speed, violence and machines.

The artists were deliberately and aggressively revolutionary in the use of materials and

techniques. They took materials from Pointillism and, much later, from Cubism, where they

came up with multiple images in one composition.

5

Radical approach to art creation was witnessed during the World Wars when some Swiss

artists under the Dada Art Movement sought to overturn what they regarded as ―outworn

aesthetic standard‖. The group individually appropriated large portions of unconventional

materials for art creation. They believed that art could be made of anything, even rubbish

(Reid, 1975). Gradually, the excitement that was expressed by the public at the emergence

of the movement lost its power to shock any longer. Other Dada artists like Max Ernst and

Ben Nicholson exploited the environment and came out with materials as mugs, jugs and

bottles as suitable materials which they used for their art expression. According to Getlein

(2002) the artists loved these materials because of their simplicity and the fact that they

were well known to everyone and could be understood from a simple profile. Artists

continued their search for the best means of expression as best as they could. For instance, a

French painter, Jean Dubuffet, developed a very different but distinct form of art expression.

His art creation was inspired by what he called ―Art Brut‖ (raw art), where materials of

uncommon backgrounds were mixed with tar, sand, and mud and manipulated to produce

works.

The tempo of radical changes in Europe and America opened up a modern epoch in art

creations. Artists from Europe who settled in America because of the World Wars continued

the quest for new concepts, materials, and techniques. New York School played a major role

in the emergence of new concepts of art expression in America and beyond. For instance,

Jackson Pollock, one of the outstanding abstract Expressionists, rejected much of the

European art tradition of aesthetic refinement for cruder and rougher materials, an approach

akin to Jean Dubuffet of France except for their materiality.

Gina (2007), states that where there is an idea, there is a way to express it (irrespective of

which part of the world the artist is coming from). To do this, artists exploited the

6

environment and created art out of non-regular materials just to portray their love for art and

the skills employed in its expression. For instance, Anastasia Elias used toilet paper rolls to

create miniature scenes of life. In a similar development, Erika Irish Simmons liked to

gather and preserve old technology such as cassette tapes that were no longer being used.

She used these unconventional materials to create popular celebrity portraits. Stanislav

Aristov from Russia used burnt matchsticks and bent them to his desired shapes before

editing photographs of them via Photoshop, where delightful scenes were created. In another

development, old watch parts were the most suitable materials used by Susan Beatrice to

create steam punk sculpture. She mainly used recycled parts which coincided with her love

for nature. Another innovative artist was Kseniya Simonova, who used sand to create

animated stories. From the pile of sand, the artist could push, rub and pinch sand into

accents that translated into beautiful depictions. Paul Vilinski is another visual artist that

used discarded materials such as beer cans to bring out his artwork in meaningful poetic

ways. The artist‘s concern for environment issues can be seen in his works, as he often used

recycled materials, giving them new breaths of life as art pieces.

Grant (2009) observes that with the introduction of new materials, the admixture of the

materials and the fair number of exploration, as well as experimentations by artists, fresh

reasons for new art movements were being stimulated. The author stressed further that

artists were in search of unique and best materials and techniques to express themselves, and

to communicate with the public. The new discoveries and inventions accelerated the pace of

art redefinition and development as newer and better media of expressions kept coming to

limelight.

The impact of the artistic transformation went beyond the boundaries of Europe. This was

first felt in the regions colonized by the individual European countries. This became

7

possible because of the relationships established through the policy of colonization. The

non-European world began witnessing inflows of cultures strange to them. Gradually, the

western nations established their kinds of values in these territories. The world started

witnessing the interpretation of artistic issues from a western world view point. In Africa,

for example, and especially in Nigeria, one fact that seems settled is that the European style

of art expression as known today evolved with Aina Onabolu (1882-1963), who not only

excelled, but who also carved a niche for himself in pioneering art education in the country.

It is observed that before 1910, not much was going on in terms of modern (European

technique) art expression in the West African sub-region. Before then, Nigerians were

creating purely indigenous arts, free of influence by any outside art-making ideas. Works

interlaced with the basic materials to create art used as a vehicle to convey spiritual concerns

for survival (Egonwa 1994).

Babalola (2004) notes that Nigeria has a flourishing art history, and that before Onabolu

could venture into the European art expression, he had interacted with, and was used to, the

types of forms in Nigeria, as art was highly appreciated by the Nigerian people. Also,

Babalola posits that Onabolu knew that the Europeans did not believe in the art of the

people. Nonetheless, he was not deterred, but was committed and determined, to reproduce

the works as he saw them. This success ended the initial error held by Europeans that no

African person was capable of producing the kind of art works created by them. Onabolu‘s

effort earned him a scholarship to read art in England and France. At the end of his study, he

did not only excel as a painter par excellence, but carved a niche for himself.

When Onabolu returned from studying overseas, Art was introduced to be taught in schools

alongside other subjects. Despite initial difficulties faced as a result of lack of teachers,

Onabolu was determined to succeed by moving from one school to the other to be

8

personally involved in the teaching. Grillo in Ikpakronyi (2003) notes that Aina Onabolu

had sacrificed so much for the survival of the subject when states thus:

The period of inertia was during the period of Onabolu. Nobody appreciated

what he was doing. He was going from school to school teaching and getting

almost nothing and trekking from place to place. He lived more or less as a

pauper. Well, relatively he didn’t have much and he died more or less just

like a school teacher. His works of course are now being appreciated.

The initiative by Aina Onabolu and those who later worked with him (Kenneth Murray, H.

E. Duckwork, Dennis Duerden and J. D. Clarke), and the impact they made, perhaps

prompted Konate (2004) to refer to them as ―instrumental figures‖. This feat marked the

official use of conventional and academic European materials, techniques and styles of

executing art works in Nigerian schools. The combined efforts of these art teachers

produced budding and talented artists like J. D. Akeredolu, Akinola Lasekan, C. C. Ibeto,

Ibrahim Uthman, A. P. Umana and Ben Enwonwu. These artists individually made their

distinct landmarks in the propagation of visual arts. Aina Onabolu, however, apparently

dominated the contemporary Nigerian art scene for about two decades from the 1920s to the

1940s, and he continued to dominate until his death in 1963. Today, he is generally not only

regarded as the father of modern art and art education in Nigeria, but he lit the torch for a

dynamic contemporary art in modern Nigeria. The subject was further strengthened, when

Ben Enwonwu (1921-1994) who graduated from Slade School of Art in London, was

appointed the Federal Art Advisor. He, like Aina Onabolu, was exceptionally talented and

committed. He initiated and introduced a new concept (which was later known as natural

synthesis) in his art expression. He dominated the Nigerian landscape with innovative works

for about a decade (Babalola, 2004).

The first set of students in the persons of Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Bruce Onobrakpeya

and others, were admitted into the Nigerian Collage of Arts, Science and Technology, Zaria

9

(now Ahmadu Bello University) in 1957. Art courses were made professional, based

entirely on the conventional academics of the European approach. Ikpakronyi (2009) notes

that the Europeans formed the bulk of the teaching staff and the programme came into real

focus. The students who were not satisfied with the European style of expression sought to

discontinue with the conventional approach. They gradually continued to distance

themselves from the Western artistic concepts and historical experiences that were alien to

them. They felt the need to create an identity to the African artists. Those who spearheaded

the desire for the change included Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, among others. On what

appears to be a justification for the step they took, Onobrakpeya (2003), one of the frontiers

of the Zarianists, states that the whole idea behind their activities was to save Nigerian

civilization and to salvage the personality of her people from the inferiority complex which

was the outcome of colonialism. He singled out Uche Okeke, who had experience in the

documentation and collection of folk art pieces, as their leader and states thus:

With his background, we were not surprise that Uche became the leader the

now famous society while still at the college. The members of the society

were guided by the synthesis concept, he advanced. Synthesis was recourse

to the root of our timeless values, which should be married to equal good

foreign values… It was in short, to create a rich artistic presence and a

hopeful future. As the Zaria Art Society left the college and dispersed to

different parts of Nigeria and abroad, the Synthesis Theory became cardinal

in their practice as painters, sculptors, teachers, media artists etc. This

widespread new artistic energy created a new renaissance, with respect to

the artist and the art in general.

Uche Okeke confirms their instructors‘ relegated Nigerian cultural values to the

background. He affirmed his leadership position of the Zaria Art Society when he also states

thus:

I was myself a member of the Zaria Art Society and its chairman from 1958

to 1961,…when most of its founding members graduated…The majority of

our instructors were British or British trained and we students opposed to the

system of teaching art subjects that ignored Nigerian cultural values,

10

restricted their method of imparting art knowledge and their preoccupation

with the study of nature, which in our view, was superficial.

When the Zaria Art Society was formed, the group used to meet formally and informally to

discuss the socio-cultural existence of the creative artists in the throes of change. Again, the

leader (Uche Okeke) in an interview granted Chika Okeke on the 31st August 1997 stated,

―We wanted to show Nigerian art and also have a distinct Nigerian character rather than

posturing as colonial transplant.‖ In another development, Oshinowo (2008), notes that the

formation of the Zaria Art Society was founded on a profound desire for political freedom.

He believes the formation fuelled the spirit of individualism in all members, and also

infused in their minds national consciousness and cultural pride. The author explains further

that the spirit of individualism culminated into a synthesis of indigenous and Western ideas.

The philosophy of natural synthesis was intensified, which later influenced almost all

succeeding generations of Nigerian artists and their art creations. Perhaps the doggedness of

the students in creating new consciousness, which ushered in what Filani in Konate (2004),

refers to as ―New African‖. In his study of the works of the graduates, Oloidi (2009)

observes that the pioneering students had acquired aggressive artistic radicalization of the

Zaria revolutionaries between 1958 and 1961. He observes that it prepared the foundation

for a solid artistic standard in modern Nigerian art.

Generations of artists keep expanding the boundaries of art expression as they seek new

vocabularies, materials, and techniques that enable them address new concerns. Diarra

(2017) contends that Africa‘s art scene is characterized by innovation and conceptual

profundity which has paved way for the next generation. Materials of different backgrounds

are used to create works to interpret and portray the society‘s socio-economic realities,

political challenges, rich tradition and diverse beauty. For instance, the Zaria Art Society

11

advocated Natural Synthesis for Art Expression which was a fusion of African motifs,

concepts and techniques with Western ideas (Ekpo, 2010). This concept led to other

experiments that developed with time. Individual artists over the years have appropriated

different unconventional material and techniques to express their feelings. Explorations and

experiments, earlier started in Zaria, brought radical reformation in art expression in

Nigeria. Nwoko‘s sculptural work with other artists of the Zaria Art Society caught the

attention of other contemporary Nigerian visual artists, who appropriated relevant materials

to address issues of the moment. Worthy of note is the Nigerian civil war, one sad event that

inspired artists with the Zaria Art Society members, particularly from the Eastern part of the

country (such as Uche Okeke, Obiora Uchechukwu, Chike Aniakor) who used their creative

abilities to react to the avoidance and the waste of the war.

Sowole (2013) observes that Alex Nwokolo metamorphosed from the use of one medium to

the other in his quest to be unique. The years of experiments in different media like Jean

Dubuffet of France, has made his art expression stronger. The author sees Alex Nwokolo

among the generation of Nigerian artists who have transited from one radical media to the

other, yet is still making impact. Sowole quotes Nwokolo thus:

The desire for change and the need to have a global perspective in my art

instigated a stimulus for this current direction in the evolution of my work.

The new experiment and materials offered me yet another opening to

contribute to an existing international calligraphy…and media derived from

everyday socio-cultural signs and symbolism, where elements are assembled

and dissected on to a surface resulting in a hybrid painting and sculpture.

In 1990, some young artists who christened themselves as Nogh-Nogh Art Group, a group

which included Danjuma Kefas, Babalola Tunde, Ayo Aina, Lasisi Lamidi, among others,

from the Fine Arts Department of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria became worried because

of the attitude of the public towards the types of artworks created by them, as they mostly

12

appropriated unconventional materials found in the environment. The group is experimental

in nature, and has embarked on organizing periodic workshops, seminars and exhibitions of

their works, with participants coming from all over the country. The peculiar nature of their

art creations attracted sympathy from other members of the community. Most of those who

shared in their ideology joined them in their regular meetings (Jari, 1994). It was in one of

the meetings that the group adopted the name Nogh-Nogh Art Movement. The word ―NoghNogh‖ is a derivation from the Nupe language, and means ―nonsense‖ (Jari 1994).

According to Danjuma (2002) one of the leaders of the movement, stated that from

inception the movement has always had unconventionality as its main goal. As the

movement kept growing, other goals such as creation of forums for discussion, and for the

propagation of the works of the members, were developed. Different found objects were

adopted by the participants in their art creations. This policy of freedom of expression

adopted by the movement has not only popularized the movement, but also attracted more

members. Members are further encouraged to appropriate materials and styles they think can

best express their feelings, and it did not seek to influence the adaptation of a particular

approach by its members. The group encourages simplicity of materials in all aspects of its

operation. Danjuma (1994) in his assessment of the activities of the group, contends that

their activities have positive effects on the artistic thinking of people who have come into

contact with them.

Another artist known for his experimental work in various materials within Nigeria and

beyond is the Ghanaian born sculptor, El Anatsui, who resides in Nigeria. Angie (2017) and

Diarra (2017) have individually written and alluded that El Anatsui is one of Africa‘s most

influential mixed-media artist, although he was trained as a sculptor. The artist has spent

much time in Nigeria, teaching at the University of Nigeria Nssuka. He uses different

13

unconventional materials as he could find them suitable and makes exquisite objects of

stunning visual impact. More recently, El Anatsui turned to installation and more complex

sewing techniques, which enable him to create art using unconventional materials like liquor

bottle caps and discarded pieces of metals for his large-scale assemblage art.

A Non-Governmental Organization striving hard to increase and develop the creative

abilities of artists in Nigeria is the Bruce Onokbrakpeya Foundation (BOF). It is an artist-led

organization formed in 1985, with a mission to engender the growth of art culture through

the provision of opportunities for artists to improve themselves through skills acquisition

and empowerment. Ekpo (2010) observes that since its inception, the Bruce Onokbrakpeya

Foundation has been an enduring player in the visual arts scene in Nigeria. The Foundation,

through its Annual Harmattan Workshop, encourages artists to use their creative powers

through appropriating any materials and techniques at their disposal to create. Works

produced at the end of the workshops are exhibited in different places. For example, it has

organized the Amos Tutuola Show, Lagos (2000), participated in the Commonwealth Heads

of State and Government Meeting (CHOGM) Exhibition, Abuja (2003), Art and

Democracy Exhibition, Asaba (2004) and the Harvest of the Harmattan Retreat Exhibition

organized in collaboration with the Pan Africa University, Lagos (2004). In 2012, the

Foundation featured the works of 20 artists at the Exhibition Bruce and Harmattan

Workshop Experiment at Kajino Station in Dakar, Senegal during the 2012 Biennial

Conference.

In 2005, another art group christened Art Is Everywhere emerged at the Nigerian art space.

The leader of the group is Ayo Adewumi, a lecturer at the Institute of Management and

Technology (IMT), Enugu. Membership of the group is made up of students and staff of

different institutions who share their ideology. As the name implies, they believe that art is

14

found everywhere and the environment has to be properly exploited. The group encourages

its members to scavenge the aquatic, creeks, mountains and the streets for materials for art

expression. Sowole (2003) in his study of the group, notes that their approach to art creation

is at sharp contrast to the regular art studio environment. The author observes that their

materials range from the wastes of electronic and electrical materials being assembled into

sculptural pieces to the plastic waste combined with other materials into figural renditions.

The emphasis of the content of the art of the group is on waste recycling and providing

avenues for training young artists and the less privilege on how to make a living from

recycling items. Since its inception, the concept has gained much acceptance and is

expanding in scope. The group has adopted A Travelling Workshop Policy to create public

awareness. The workshop has spread to places like Enugu, Jos, Kaduna, Zaria, Lagos, and

Port Harcourt.

Contemporary Nigerian artists who appropriate unconventional materials strive to sensitize

the public on the viability of waste and found object as potent creative resources. They also

facilitate its practical engagement to budding artists. Artists have continued in the search for

the newest material and techniques using any kind of materials, including unconventional

media and techniques, to create new aesthetics. Some sections of the public still see the use

of unconventional media as a revolt against established standards of art creation (Gushem

2005).

Statement of the Problem

It true that bad economy of a country is one of the factors that affect creativity, but even

when the economy is good, some artists enjoy expressing themselves appropriating waste

products as their first choice. Today in Nigeria, art produced in unconventional materials

largely comes from waste and discarded materials. Works in these materials are subjected to

15

different interpretation. Odoja, Makinde, Ajiboye and Fajuyibe (2013) have expressed the

view that ―waste or junks are considered to be useless, discarded materials that are no longer

good enough and, therefore, need to be disposed as unwanted.‖ In the society, some people

have developed a mind-set that any material found in a location designated as rubbish is

concluded to have outlived its usefulness and is, therefore, irrelevant. People with that kind

of mind-set see such work as inept and a fraudulent means of art creation. They consider the

products as works without any artistic effort, even when elements and principles of design

are applied.

Gushem (2005), notes that, the use of waste for art creation (by people who have

preconceived thoughts on what art should be), is contradicting and against established

standards. Saliu (2005) admits that art products are capable of generating excitement as well

as controversy. Vigorous enlightenment embarked upon (by art historians through their

write-ups, groups like Bruce Onobrkpeya Foudation (BOF), Nogh-Nogh Art Group, Art is

Everywhere Project among others, to draw attention to the potential of waste materials for

art expression.

The problem of the study is that there are still arguments for and against works of art created

using unconventional materials in Nigeria. The conflicting views for or against art

productions in these materials are clamoured by some viewers including some artists. This

indeed is a controversy in the creative landscape. The study is therefore set to analyze, using

the works of the artists under study, in order to come up with a clear position on the

opposing opinions.

16

Aim and Objectives of the Study

The aim of the study is to encourage upcoming artists to be open-minded in the use of

materials in their creative expression, while the specific objectives are to:

i. examine the backgrounds of the artists being studied;

ii. investigate the motivation for their use of unconventional materials in art

creations;

iii. interrogate what informed the artists‘ courage in art creations with

unconventional materials;

iv. find out the relevance of the thematic concerns in their individual compositions;

v. make comparative analysis of the materials the artists individually used; and to

vi. draw conclusion from the findings and suggesting direction of which creation of

art work should take as regards to the use of materials.

Research Questions

The study makes use of research questions for the collection of the data. The following

questions are formulated to guide the researcher towards the solutions to the problem, as

recommended by Leuizinger (1976) and Egonwa (2012).

i. What are the artistic backgrounds of the artists being studied?

ii. What motivated their use of unconventional materials their creations?

iii. What informed the artists‘ continuous art creations in unconventional materials?

iv. How relevant are the thematic concerns in their individual works?

v. How similar or different are the materials and techniques the artists used?

vi. Which material is most suitable for art expression?

17

Justification of the Study

One of the challenges of the moment in art creation, is that imported art materials are

expensive in the market. Artists who continuously depend on these imported materials are

likely to be creatively frustrated and consequently rendered out of practice due to the cost of

the importating the materials. The experience of the French Expressionist painter, Jean

Dubuffet (1901) is a good example, when he explored and experimented with new and

crude materials that were not popular at that time. The works were derided, hated and

rejected. He and his colleagues took courage and kept exploring and experimenting. At the

end, they came up better and stronger. It therefore, takes the courage of an artist to gather

materials from unaccustomed environment and combine them in a new context.

From the experience of Dubuffet (1901) the French Expressionist painter whose works were

only later appreciated, Nogh-Nogh brought on those that come in contact with the group as

expressed by Kefas (1994), and the success of the Art is Everywhere project, expressed by

Odoh, George, Odoh, Nneka, Anikpe and Ekeke (2014), show art expression matures with

constant explorations and experiments. The copiousness of the unconventional materials

creates an opportunity for continuous experiment and exploration. Therefore, artists need to

exploit their aesthetic potentials for their art creations. The artists would freely exercise their

rights to freedom of expression, and discover new ways of transforming and representing

new concepts.

Significance of the Study

The significant of the study is that manipulating waste and found objects (which constitute

major materials used by the artists under study) into works of art, shows the innate creative

potentials that such materials possess. Unconventional materials exist in diverse forms and

18

are either man-made or naturally occurring. Generally, waste materials anywhere command

global attention as a result of its role in environmental degradation. Growing concerns on

climate change have made waste generation and management a topical issue. Perhaps this

made Ganiyu (2011) to state that one of the concerns of the environmental scientist is the

management of waste products, while another concern is to draw the attention of artists to

the realization that every geographical location is rich in the copiousness of materials for

artistic expression. Olbrantz (2006) is delighted that artists have explored the use of

different industrial wastes in producing art forms that are not only visually appealing, but

also environmentally friendly.

In the search for creative fulfillment, artists who have seen the creative potentials of these

materials have consistently explored the environment as a useful source of materials for

creative concepts. The materials are available and obtained with ease; the cost of production

is less; the materials provide new aesthetic windows for visual activities, thereby

encouraging entrepreneurship among adherents of the concept. Also, recycling of materials

into new contexts is encouraged.

Scope and Delimitation of the Study

In the search for self-expression and creative fulfillment, the artists have consistently

experimented with wide range of materials as useful sources of ideas and materials. This

indeed is a wide subject considering the number of artists practising with different media.

Therefore, to carry out a comprehensive study of materials, there is the need to restrict the

study to a manageable scope, hence the choice of unconventional materials. The study is

further restricted to artists who remain consistent in using the unconventional materials for

their expressions. Nine (9) artists trained as painters and now using unconventional

materials to express themselves were selected. The study is delimited to their works in

19

unconventional media that are accessible within Nigeria, most especially those in their

studios, homes and galleries.

The selected artists are Ayo Adewunmi, Ayo Aina, Ikechukwu Francis, Jerry Buhari, Mabel

Chukwu, Ndidi Dike, Nkechi Nwosu Igbo, Nsikak Essien and Sussan Ogenyi Omagu. The

reasons for the choice include: (i) constancy in the use of wastes in artistic production (ii)

creativity use of waste materials into new and unique context (iii) courage in the continuous

use of unconventional materials; and (iv) the fact that works produced addressed sociopolitical, religious, economic and environmental issues that impact on the lives of Nigerians.

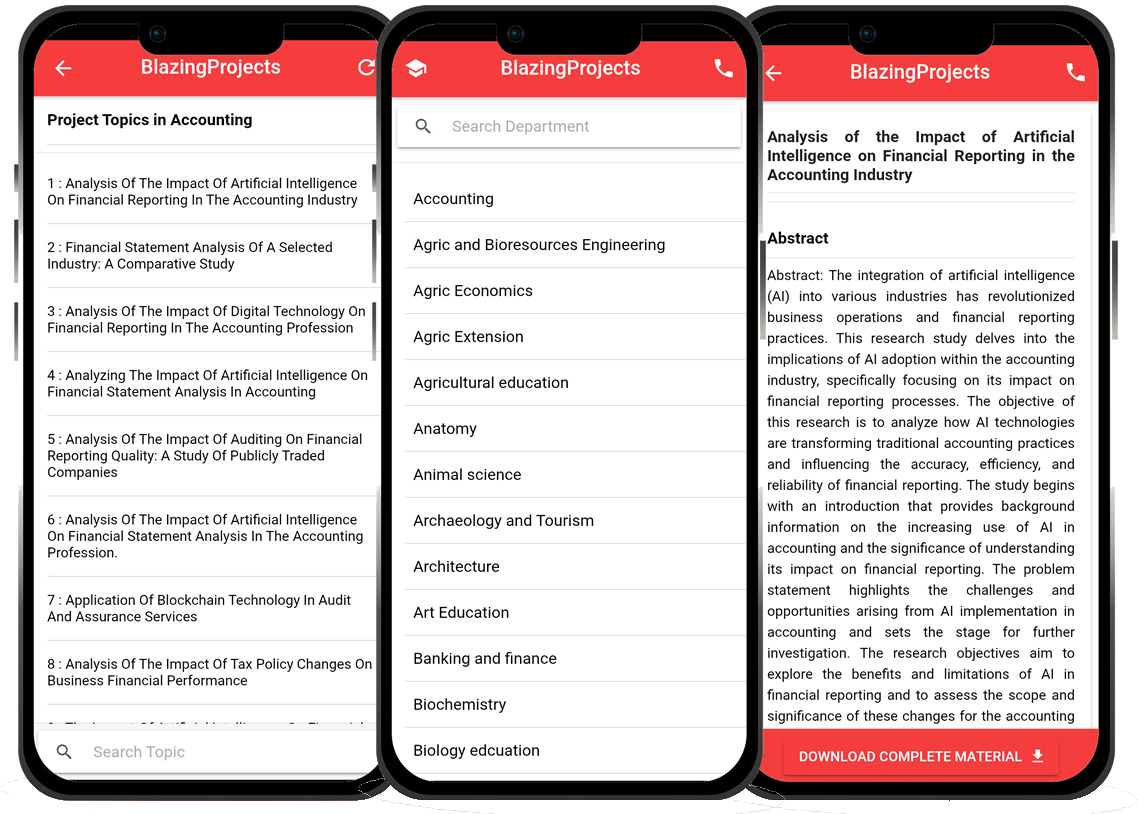

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Impact of Digital Art Platforms on Art Education in Secondary Schools...

The research project, "Exploring the Impact of Digital Art Platforms on Art Education in Secondary Schools," delves into the transformative effects of...

Exploring the Impact of Digital Technology on Art Education in Secondary Schools...

The research project titled "Exploring the Impact of Digital Technology on Art Education in Secondary Schools" aims to investigate the influence and i...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education...

The project, "Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education," aims to investigate the influence of virtual reality (VR) technolo...

Investigating the Impact of Digital Technologies on Creative Learning in Art Educati...

The project titled "Investigating the Impact of Digital Technologies on Creative Learning in Art Education" aims to explore how the integration of dig...

Exploring the Impact of Visual Arts Integration on Student Learning in Elementary Sc...

The project topic "Exploring the Impact of Visual Arts Integration on Student Learning in Elementary Schools" aims to investigate the effects of incor...

The Influence of Technology on Teaching Art in Secondary Schools...

The project topic "The Influence of Technology on Teaching Art in Secondary Schools" delves into the intersection of technology and art education in t...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education....

The project titled "Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education" aims to investigate the effects of incorporating virtual real...

Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Art Education...

Overview: The integration of technology in education has revolutionized the traditional teaching and learning methods across various disciplines. In the realm ...

The Impact of Technology on Art Education: A Case Study of Virtual Reality in the Cl...

The Impact of Technology on Art Education: A Case Study of Virtual Reality in the Classroom Overview: Art education has always been a dynamic field that contin...